Keeping a stable and moderate level of inflation is important for a healthy economy. Therefore, there is value in understanding not only how overall inflation is evolving but what is driving it. Knowing why inflation changes in any given month requires looking beyond the headline number.

To get a fuller picture of this evolution, the SF Fed details the contributing factors underlying the consumer price index (CPI) in its new data page—CPI Inflation Contributions from Goods and Services.

Why dive into CPI inflation?

Inflation measures mainly differ in how prices are calculated and what basket of goods and services is chosen to represent typical American household spending.

The Federal Reserve states that the personal consumption expenditures price index (PCEPI) produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis is most consistent over the long run with its statutory mandate (Board of Governors 2024). In March, the San Francisco Fed released a data page with a number of indicators disentangling the contributions of different groups of goods and services to the PCEPI. However, PCEPI is not the only inflation measure that economists look at.

Another commonly used inflation measure in the United States is based on the CPI, which is released monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The PCEPI and CPI share many of the same features, as they are both designed to track the prices of goods and services consumed by households and thus include much of the same data.

However, the CPI differs from the PCEPI on many dimensions. The most meaningful difference is the share of each consumption basket that is taken up by various goods and services. In particular, the CPI puts less weight on the cost of health-care services than the PCEPI but more weight on the cost of shelter (Cao and Shapiro 2013).

The evolution of CPI contributors

The new CPI Inflation Contributions from Goods and Services data page provides monthly updates on broad and granular categories of CPI inflation and highlights its biggest drivers.

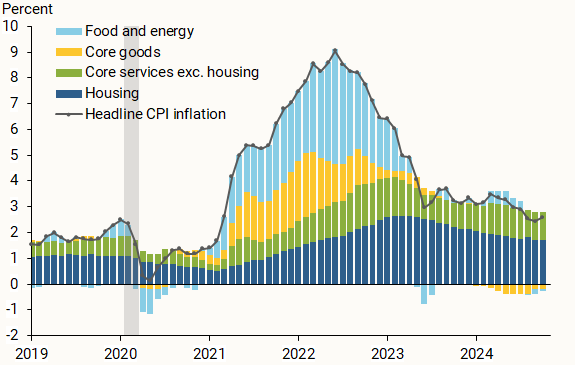

The broad categories of goods and services in Figure 1 show that energy and food prices (light blue bars) contributed to much of the overall CPI inflation from early 2021 through early 2023. However, these contributions have decreased significantly since then, as energy prices broadly fell from their 2022 peaks and food prices grew at a relatively slower pace.

For most of the past two years, housing costs such as rent have become the largest contributor to year-over-year CPI inflation (dark blue bars). This reflects that inflation in this category remained elevated as inflation in other categories, such as core goods (for example, used vehicles), moderated notably (gold bars).

Figure 1

Contributions to 12-month headline CPI inflation

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and authors’ calculations.

Diving deeper into core CPI contributors

In addition to separating CPI inflation into these broad categories, the data page provides a more detailed breakdown of core CPI inflation, which excludes the volatile food and energy categories. This granular breakdown allows us to see the specific contributions from goods and services that have been driving inflation up or down.

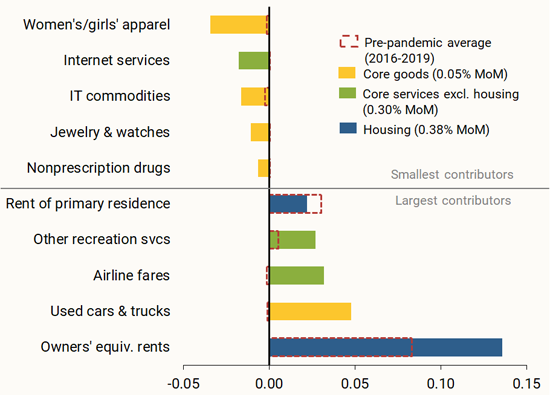

Figure 2 presents this breakdown for month-over-month core CPI inflation in October 2024, focusing on the five largest and five smallest contributors out of 67 total subcategories. The remaining contributors not shown here are available in a downloadable data file on the data page.

Figure 2

Smallest and largest contributors to core CPI inflation: October 2024

Consistent with Figure 1, we see that some of the largest contributors to month-over-month core CPI inflation are related to housing services (blue bars). In October, declines in the prices of internet services and some goods, such as tech gadgets, jewelry, and prescription drugs, helped partially offset the large monthly increase in contributions related to used vehicles, housing, and other services categories such as airfares and recreation.

The new data page will be updated monthly, shortly following the CPI data release by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2024.“Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy.” Adopted effective January 24, 2012; as reaffirmed effective January 30, 2024.

Cao, Yifan, and Adam H. Shapiro. 2013. “Why Do Measures of Inflation Disagree?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2013-37 (December 9).

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.