At the San Francisco Fed, we are students of the economy. We monitor ongoing and future risks to the economy, including climate risk. The economic impacts of a changing climate—including the frequency and magnitude of severe weather events—affect each of our three core responsibilities: conducting monetary policy, regulating, and supervising the banking system, and ensuring a safe and sound payment system.

“We have to be more thoughtful about how to make every drop count,” said California Governor Gavin Newsom in a May meeting with leaders from the state’s largest urban water suppliers. He warned that California could be forced to impose mandatory cutbacks throughout the state due to severe drought.

In April, Utah’s Governor Spencer Cox declared a state of emergency due to the dire drought conditions affecting the entire state. “Once again, I call on all Utahns—households, farmers, businesses, governments and other groups—to carefully consider their needs and reduce their water use.”

Of course, it’s not just California and Utah grappling with a record drought. With drought comes economic consequences, including increased fire risk, water restrictions, increased insurance costs, and much more. Of course, it’s not just California and Utah grappling with a record drought—impacts are being felt across the Twelfth District. According to the journal Nature Climate Change, the megadrought in the Western United States has produced the region’s driest two decades in at least 1,200 years.

Here’s a look into drought-related impacts felt in the district during the first quarter of 2022:

Intensity of Drought Worsens

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, nearly 95% of the Western region was experiencing drought conditions. As a result, the district has seen declining water supplies from the Colorado River and several other watersheds and had already begun to experience intense wildfires. The link between drought and wildfires is complex. According to the National Integrated Drought Information System, drought can be a contributing factor to wildfire. Dry, hot, and windy weather combined with dry vegetation (due to decreased snowpack and streamflow, dry soils, and large-scale tree deaths) can increase the chance for large-scale wildfires.

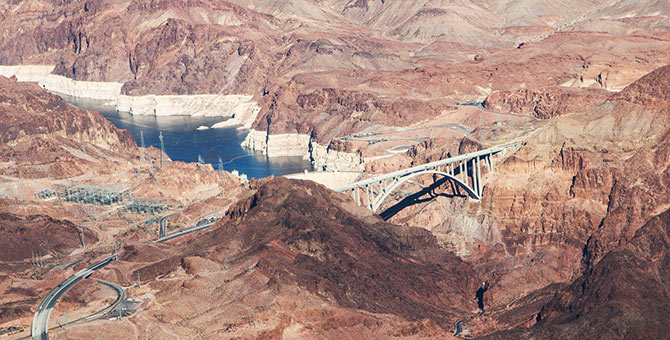

Federal water managers declared the first-ever water shortage along the Colorado River last year, triggering cuts to some of the river’s 40 million users. The Great Salt Lake has lost half of its water in the last 150 years and Lake Powell’s water level is down 28 feet from last year. Through May 1, California’s aggregate intrastate storage reservoirs were nearly 30% below average and those that originated from out-of-state (including the Colorado River) were only half of average historical levels.

Most land area in the Drought Monitor’s West Region remained in drought through May 3. In much of the district, the intensity of drought had worsened since year-end 2021 due to a dry Spring. Forecasts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Interagency Fire Center suggest that drought will continue, and wildfire risk will remain heightened in the majority of the District. Notably, most of California’s most destructive fires since 1991 have occurred in the past five years, setting an ominous precedent.

Dry, windy conditions have already contributed to elevated wildfire activity in 2022. Year-to-date through June 13, the National Fire Information Center had tracked 29,827 fires that had burned more than 2.6 million acres nationwide, well above a 10-year average of 23,070 fires and 1.1 million acres. New Mexico and Texas drove more than half of the year-to-date land area burned, while district states accounted for roughly 29%, led by Alaska. As we head into “fire season,” the level and breadth of fire activity in the district will likely increase. For instance, during 2021, Twelfth District wildland fires consumed more than 5.1 million acres, representing 73% of all wildland fire acreage nationally.

Figure 1

Drought Severity, West Region

Increased Risks in the Twelfth District

As many Westerners are aware, drought poses an increased risk of wildfires to their homes, businesses, and communities. In addition, it creates unique economic challenges for borrowers reliant on water quality and accessibility, such as farmers, ranchers, food and beverage producers, hydropower generators, metals miners, and water recreation-related businesses (e.g., centered around lakes or rivers). Although most banks in the Twelfth District do not directly hold a high concentration of agriculture and farmland loans, they are exposed to economies centered around agricultural activity, for instance, in California’s Central Valley, western Oregon, eastern Washington, southern Idaho, and portions of other district states. According to the USDA Economic Research Service, “in regions that rely on rainfall for agricultural production, drought can diminish crop and livestock outputs and may severely affect farm profitability. Drought also reduces the quantity of snowpack and streamflow available for diversions to irrigated agricultural land. These impacts can reverberate throughout the local, regional, and national economies.” They went on to classify, as of March 8, 2022, more than 20 percent of land in the Western states as experiencing extreme or exceptional drought.

Banks throughout the District face financial and operational risks in the event of wildfires as they may have to restrict operations for branches in fire-prone or evacuation zones. Fire insurance offers a layer of protection for real estate collateralizing loans, but as many homeowners are aware wildfire activity has affected the cost and availability of hazard insurance, which could potentially put pressure on real estate values in certain areas.

In absolute terms, California has the most at-risk properties in the district because of its large size; however, the relative share of properties at risk may be higher in other district states. For instance, CoreLogic’s 2021 Wildfire Report indicates that the percent of housing at elevated risk in the event of extreme wildfire activity is higher in Idaho, Utah, and Nevada than in California.

For more details on economic and banking conditions across the District, visit the full First Glance 12L 1Q22 report.

Elizabeth Lawson-Kurdy is the communications lead for Supervision + Credit on the Communications + Experience team at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

You may also be interested in:

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.