Saturday, Mar 04, 2023

10:00 a.m. PT

Princeton University

Princeton, NJ

Mary C. Daly’s Keynote Closing Remarks at Princeton University Griswold Center for Economic Policy Studies Symposium

Transcript

Stephen Redding:

Good afternoon everybody. I’m sorry to be interrupting lunch, but I would like to sort of begin by thanking everybody for coming to this fantastic symposium this weekend on inflation, where are we now, and where are we heading? Just to thank all of the participants for what I think you all agree has just been a terrific discussion about this really important set of issues. We are really honored today to have, as our keynote speaker, Mary Daly, the president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the largest and most diverse of the Federal Reserve districts. Just remind everybody that Mary’s comments are going to be on the record, and we’ll also live stream on YouTube. So in the Q&A, when you ask your questions, we’re live online around the world. Mary became president and CEO of the San Francisco Fed in October, 2018, building on a long and distinguished career at the Bank that began in 1996.

She’s also held multiple leadership positions at the bank and within the Federal Reserve System more broadly, including chair of the San Francisco Fed Diversity and Inclusion Council and Executive Chair of the Federal Reserve Systems Committee on Research Management. An important focus of our early research was on the labor markets and wages and inequality, which as we all know, and related to the discussion of the symposium today, are kind of crucial when thinking about inflationary prospects and inflationary expectations going forward as thinking about those labor market issues. Mary is someone who’s dedicated to public service and has supported a large number of other public service roles, including the Congressional Budget Office, Social Security Administration, and the Office of Rehabilitation Research and Training where she’s all served on the board of all of those institutions.

As an economist, Mary is published widely on a range of topics, including, as I mentioned, wage growth and income inequality. So we’re really looking forward to her talk today on the subject of our symposium. She’s going to speak for around 30 to 40 minutes. And again, we’ll have some questions some time afterwards for questions and answers. And so Mary, without further ado, it’s a delight and an honor to hand over to you.

Mary Daly:

Okay. I share a trait with Treasury Secretary Yellen in that I need to stand on a stool to see over the podium, but you couldn’t do worse than sharing a trait with the Treasury Secretary. So thank you so much for inviting me, and Steve, and thank you for that introduction. I did want to share two things before I start my talk. The first is that I had an opportunity, a privilege actually, to meet with some of the team members from the Fed Challenge team. And I want to assure everybody in the room our future is in good hands. I think they’re may be actually interested in perhaps leading federal reserve policy someday, our monetary policy, but if not, they’ll do other things in leadership, so our future is secure. The second thing I’d like to say is that you get to the end of a conference and you say, what is the setup going to be and how much will I have to change my talk to think about that setup?

But I have been very fortunate because the conversations we’ve had so far have provided many of the details that will inform me in the remarks I’m going to make today. So I feel like I’m in a great position, and that has been a pleasant surprise. As you’ve gone to many conferences, you know it’s not always that way. So let me start then with the thing that’s on my mind. The most frequent question I’m asked these days, literally it is the most popular question that I get asked, is what will the Federal Reserve do next? And I understand people are actually worried. Inflation is still high, and the FOMC has been taking aggressive policy action to bring it down. And the responses to our actions range from fearing that they will tip the economy into recession to fearing that they won’t work at all and the job will never be done.

And for most people, such a wide range adds up to a tremendous amount of uncertainty, and the impulse to look for answers in the immediate, the next meeting of the FOMC, the next data release, the next market update. And honestly, it doesn’t help that we all face a constant barrage or ground the clock ticker tape news, financial and economic. But achieving our mandated goals at the Federal Reserve requires that we take a broader view. As policy makers, we have to respond to an economy that is evolving in real time every day, just like the ticker tape, and prepare for what the economy will look like in the future. So today in my remarks, I’m going to do just that. I’m going to pull back the lens, so to speak, from the immediate, the day-to-day, and I’m going to talk about the inflation landscape, what it looked like before the pandemic, what it looks like now from my vantage point, and what both could mean for our future inflation path.

Now, I always have to this, and it’s as good as time as any to do it, to say that the remarks I’m going to make here today are my own and do not necessarily reflect any of my colleagues or anyone else in the Federal Reserve System. So let’s get started. So to understand how future inflation could evolve, we must first remember where we were before the pandemic. So I’m going to start there. And we heard a little bit about this morning in the panel, but I want to read review it. So before the pandemic and the current episode of high inflation, the world was starkly different. The principle and decade long challenge for the Federal Reserve, and most other or many other central banks, was trying to bring inflation up to the respective targets that they had. And it wasn’t about pushing it down. Large structural forces were really to blame. The most notable that I followed was population aging, which was affecting both the labor force and savings rates in industrialized and developing nations alike.

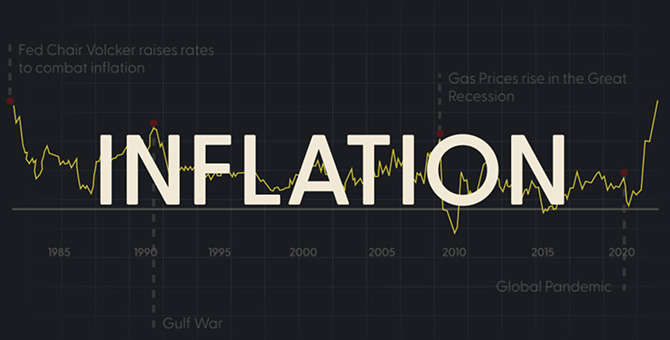

Global productivity growth was also slowing from its previous pace, and it was affecting demand for investment, which we heard Ricardo said investment demand was just low. So together, these developments brought about weaker trend growth and lower real interest rates, and they also put steady downward pressure on global inflation. Economics and policy discussions became quite focused on secular stagnation or a persistent state of little or no growth where economies struggle even to grow their potential. And top of mind for policymakers, as Bill Dudley mentioned today, was a low neutral rate of interest, the zero lower bound on interest rates, and the risk of consistently running below target inflation. So the inflation challenges in the US were pronounced, and I think it’s worth showing. So this is a picture that just shows inflation over the period of time, 2012 to current. And what this figure shows is that despite sustained monetary policy accommodation after the great recession, annual PCE inflation, which is the one we follow, remained below 2% for 84 out of 98 months, or about 86% of the time.

So that’s from 2012 to 2020. And over that same period, the federal funds rate, if you don’t remember, was set near zero, about half of that time, and below the neutral rate of interest, which was estimated by the FOMC to be about 2.5%, it was below the neutral rate for the entire period. So we have this very, very accommodated policy, and inflation never gets sustainably the 2%. So this environment, in retrospect, although we did fret about it quite a bit, honestly, and as Bill said this morning, it actually prompted us to do the framework review, it did offer many advantages, or at least some advantages. The economy was able to run consistently above estimates of potential growth, and unemployment was able to fall to near historic levels without spurring inflation. But it also came with risks. So I think as we think about the benefits, we also have to think about the risks.

And the risks were that inflation would fail to get to target in good times, which was what was happening, and then fall further in bad ones because we ran out of policy space and couldn’t push it back up. And eventually, this very event would seep into inflation expectations, reducing monetary policy space even further, and compounding the existing structural downward pressures on inflation. And there, the persistent deflation experience in Japan really underscored the thing that everyone was afraid of, and it motivated the fed in many other central banks to fight vigorously to get inflation up to target. And this that I just described was the seemingly unchangeable topography of the economy before the pandemic. And then, of course, everything changed. And we all know the story. When COVID-19 hit, the economy faltered, the feds went into action, cut interest rates, purchased long-term assets, open lending facilities, all in an effort to help bridge the economy through the very worst of the crisis, US fiscal agents took equally aggressive action, also to help bridge the people, the economy through the worst of the crisis.

And these efforts combined, the monetary and the fiscal, or apart, were unprecedented. And when you look at them, they worked to an extent. US economic growth rebounded, demand surged, and the labor market began to recover. Supply chains, on the other hand, were incredibly slow to respond. And by early 2021, price pressures were starting to build, first in a few sectors directly affected by the pandemic, and then more broadly, as imbalances between this policy supported robust demand and limited supply spread throughout almost every sector. So by the fall of 2021, inflation was high and heading higher. And the chart again, I’ll direct your attention to it, puts this change in inflation in perspective. So after averaging about 1.4% per year in the low inflation period, PCE inflation shot up to an average of 5.8% between February, 2021 and today.

And that’s a quadrupling of average inflation. So simply said, within a year, inflation went from consistently undershooting our 2% target to reaching levels not seen in more than a generation. That’s just a tremendous change in a short amount of time. So in response, and I think many of you’ll remember it, the Fed pivoted, pivoted from a stance of sustained accommodation and a forecast of sustained accommodation to one of rapid tightening, first through forward guidance, and then through conventional increases in interest rates. So we started our forward guidance in November of 2021, and then raise the interest rate for the first time in March of last year, 2022. And since that time, March of ’22, we’ve raised the interest rate at every meeting by a cumulative total of four and a half percentage points. And looking back through history, this is the fastest pace of monetary policy tightening in 40 years.

And if you look at broader financial conditions, which capture not only federal funds rate movements, but also our forward guidance about what’s going to happen next and the reduction in our balance sheet, conditions have tightened even more. The proxy funds rate, which we estimated out of the San Francisco Fed, is above six. And that is something that suggests even tighter financial conditions than just the funds rate would imply. Now this tightening, while pronounced, was and remains appropriate, given the magnitude and persistence of elevated inflation readings. Higher interest rates, as we know, help bridal demand growth and bringing it back in line with supply. And the rebalancing helps reduce inflation pressures over time. That’s how monetary policy works. And I would argue that this is what we are seeing, and I’ll direct your attention to this new figure. The economy has been gradually slowing, and there are different indicators that show this gradual slowing we could point to them. And as it’s happened, as the economy has slowed, inflation has followed. Since June of ’22, which is last year, overall inflation, which is the line under which the bars sit has been easing, falling from its highs of around 7% to its current reading of 5.4% in January.

And I see this as good news. It’s a sign that policy, monetary policy is doing its job, and along with improvements in supply, which are really happening at the same time. So both of those things are working together. We’re seeing the imbalances in the economy be reduced, and those imbalances have been helping inflation come back towards the target. But I think the picture also shows that the work is far from done. Overall inflation, that line remains well above target, and contributions from each of the inflation components I’ve plotted here, which is goods, housing and other services outside of housing remain well above their historical trend. And you can see that because you see that bards are coming down. That’s good news. Goods inflation is coming down, housing inflation is coming down, services outside of housing even coming down, but less rapidly. And all of that’s good news, but they’re all above their previous trends, their averages.

So that’s a lot of work left. In the lot of work, left category, I would also put that incoming data have been bumpy, and Jason talked about this last night. The recent PCE exam is a good example. The recent PCE data, after months of decline, headline and core inflation both picked up in January on a 12 month basis, and the monthly inflation rate in the latest release rose at fastest pace in seventh months. So to me, this suggests that the disinflation momentum that we need to see, to get sustainably back to our goal is far from certain. So if I put all of this together, it’s clear there is more work to do. In order to put this episode of inflation, high inflation behind us, further policy tightening maintained for a longer period we’ll likely be necessary. But I can’t say this strongly enough, restoring price stability is our mandate, and is actually what American people expect us to do, so we remain as an FOMC resolute in achieving this goal.

Now as we work toward that end, we must also considering, consider rather, the new world we’re entering. What will the pressures on inflation be once the pandemic shock has fully worn off? Will we return to a world where the central bank struggles to get inflation up to target now that we had prior to the pandemic, or has the pandemic left a more permanent imprint, such that the pressures on inflation now trend higher and we have to work hard to keep them at bay? So if I just put this in simple terms, are we going to keep working to push inflation up to our target, or are we going to have to grab onto inflation and pull it down to our target? And that’s a really different path of policy, depending on which one you think is most likely. And frankly, the answers aren’t yet clear, but the questions are imperative, and we must begin to think about them now, even though we’re in the midst of still trying to get through the inflation shock.

Now, I want to do that, and I want to put out four things that I think could cause the inflation trend to actually pull higher in the future. I don’t know if that’s going to happen, but there certainly are things we should think about and deliberate. And there’s really no better place to say that we should start thinking about this in an academic institution like Princeton, because it is the work that we… The Fed can’t do this on our own. We have to look to academics, other policy makers, other market participants, et cetera to really think through these issues. But I’m going to put out what I’m thinking about myself. So I start with what we already know. We know that the forces that drove the pre pandemic trend are still with us, aging of the population and slow productivity growth, and we know what the forces are that are causing this pandemic surge.

We know what’s going on today. What we don’t know is how these different forces coming from two different periods are going to evolve going forward and how they’re importantly going to interact with each other once this period of high inflation is over. So we don’t know what the confluence is going to be of these factors and what it’s going to do to underlying inflation. So I’m going to talk about the four things that I think might be important for considering that confluence. So the first is a decline in global price competition. If firms decide to reshore some or all of their foreign production facilities, cost and prices are likely to continue to rise. Now, I have a lot of conversations. One of the jobs of a regional fed president is to go all over your district, I have nine states, and also all over the nation, sometimes around the world, and talk to people, businesses, large and medium sized businesses that trade internationally and ask, what are you doing?

And I’m hearing, from many of them, that this kind of pulling back from a fully global economy is already happening, putting production near, or you’ve heard the terms reassuring, nearshoring, et cetera. So it’s happening. But in the same sentence, often time they tell me that it’s a large undertaking, as you can imagine, to revamp well-established and long-lived production networks. So I think it frankly remains to be seen how much this trend will continue and how complete it will be. The truth is global competition helps a lot of things. Comparative advantage is an actual good outcome, and so I think it’s probably not going to be complete, but it is something that we have to watch. One thing we do know that we absolutely know with certainty is that globalization has been a factor in past goods deflation in the United States. Getting things produced more less expensively has helped our goods deflation occur.

And a trend towards less global competition going forward could mean more inflation in that sector, the good sector, and that would put more pressure on overall inflation going forward. So another potential factor affecting the outlook for future inflation is the ongoing domestic labor shortage. Labor force participation fell precipitously during the pandemic and has been pretty slow to recover, especially among workers 55 and older. And these developments exacerbate the already significant downward drag on participation related to population aging. So you just have a trend that’s going down anyway, and now you’ve got an acceleration of that trend. So absent of substantial pickup in the share of working age adults, say 25 to 54, who are looking to be employed, or a large change in immigration flows, and I mean a significant change in the immigration flows relative to the pre pandemic trend, then labor force participation and labor force growth will continue to be slow, or even decline, and worker shortages will persist, pushing up wages and ultimately prices, at least in the near and medium term until businesses find other ways to work around this change in labor supply.

So inflation pressures might also move up, or could also move up as firms make a transition to a greener economy, which will require investment in new processes and infrastructure. And as firms increase their investments in renewable energy and energy efficient technologies, they are likely to pass some portion of these transition costs onto consumers, boosting inflation. The increased demand for investment could also raise the neutral rate of interest, at least in the short and medium term. So it depends. People estimate this neutral rate differently. Our star, if you look at a… So for the academics in the room or people who follow this, if you look at a standard Laubach-Williams model, you’re not going to get the greening of the economy affecting our star because it’s all long run variables, population, productivity, growth, et cetera, demographics.

But if you look at some of the DSG models that would do a shorter term or a medium term neutral rate of interest, you absolutely do see an effect because there’s been a shift in the demand for investment, and not a big change in the supply of savings. And so that would move this temporarily over the near or medium term. Those two things are important though for policy makers, because while we think of the star variables being long run, we actually have to think about whether we’re, in this case, as tight in policy as we think we are when these other things are happening that are shifting the… I’m going to fell off my little stool… That are shifting the neutral rate of interest. So with that in mind, that could be something important. One of the key things I will offer though is if our star changes, if our sense of the neutral rate of interest changes, then the importance of the zero lower bound changes, and the downward pressures on inflation that came with it.

So I mentioned that when policy space is limited, it just puts additional downward pressure on inflation. If we have a lot of policy space and that’s not a concern anymore, then you would think that wouldn’t be that factor that’s pulling inflation down below our target. So finally, I’ll give you the last factor I really think about in the future of inflation, and this one is at the forefront of my mind as a policy maker, is the possibility that inflation expectations could change. To date, these expectations at the longer run especially have remained stable and well anchored around the fed’s 2% goal. And so in other words, from my perspective, inflation psychology has not shifted, and the public’s faith in the fed’s ability to achieve price stability and are resolved to do it remains intact. But the longer inflation remains high, the more likely it is to undermine that confidence or just chip away at it, even if it doesn’t undermine it.

And once high inflation becomes embedded in psychology, it is very hard to change, as history is shown. Any or all of these factors could influence the natural tilt of inflation going forward, and then the monetary policy approach necessary to maintain price stability over time. And as I said at the beginning of this, the hard part is knowing when and how each of these factors will evolve or what force they will have relative to the strong pull that we saw prior to the pandemic with the aging of the population and slow productivity growth. So if these pre pandemic trends, the ones that pulled inflation down, reemerge as the dominant force, then our efforts to bring inflation down as a FOMC will be aided by natural forces in the economy. They’re just helping us. But if the old dynamics are now eclipsed by other factors that are just emerging, newer influences that put upward pressure on prices instead of downward pressure, then policy will likely need to do more.

We don’t know what the trend will be, but we do know that while we continue to diffuse this current inflation shock, we need to be working to gather data and research that illuminates what the likely path forward will be. In my mind, and I just say this as a general statement, that’s prudent policy making, an eye on today and an eye on tomorrow. So that’s not an easy discipline to have an eye on today and an eye on tomorrow. When things get hard or challenging or you’re off your goals and you’re right in the middle of it, it’s tempting to get caught up in the present, today’s data release, the newest projection. And it can be that way, so much so that you stop and you don’t look forward, or you don’t stop, you don’t look forward, take stock and imagine what the future could hold.

But policy making requires it. The pandemic and its shock waves will one day fully dissipate, they will be gone, and we must be ready. We can’t wait till it happens to figure out what’s going to happen. That would be a true case of being too late. So as I close today, I’ll return to the question I started with, what will the Fed do next? And here’s my answer, feel free to share with anyone. We will work on the economy we have today, and we will prepare for the economy that is to come. That’s what this moment really demands of us, and we’re up to it. Thank you.

Stephen Redding:

Thank you, Mary, for a terrific keynote presentation. That’s fantastic. We have a little time for Q&A now if anyone has any questions. And I think Dana and Kathleen have mics that they’re going to pass around.

Audience member 1:

Thank you. You made a reference to financial conditions. The prior session made references to financial conditions. So they started increasing in November, as you highlighted the change in tone, and they peaked mid-summer up 400 basis points. So that actually was a lot of heavy lifting from the financial markets for the delay in the Fed. But the lag time from that is not, people say long and variable. It’s certainly variable, but all the studies, New York Fed, academic studies, Federal Reserve Board show that the peak impact is two to three quarters. So why does everybody talk about the long lag and the variable? So some portion, but the biggest impact has already been felt. And how does that affect your view of recession?

Mary Daly:

Sure. So on the long and variable lags, we use that terminology long and variable lags because that’s what policy is. You put it in the pipeline, and then it took a while, it used to take a while for it even to trickle through to all financial markets. And then it would take a while for it to move its way through the economy, and you add all that up. And when I was coming up in macro, it could be up to two years before these things could work themselves through, 12 months to two years. So what happened in with forward guidance, I would argue a lot of this is about communication policy, forward guidance tells financial markets, we’re going to move, and here’s where we’re going. Then financial markets, and you saw this in the November 21 pivot of policy, we said we’re going to taper asset purchases faster.

We haven’t announced exactly, but that’s what we’ll likely do, and we’re going to get into an interest rate increasing program as early as those purchases end. And financial markets repriced immediately, and things tighten. And you did see almost an immediate impact in the mortgage market. Refinancing… We talked to banks and lenders all the time. Refinancing started dropping like a stone. It just started falling. And then that by the first of first quarter of ’22, you started to see this in mortgage originations, and then you started to see it in the really fast rates of home price appreciation. That started coming off. And so that was accelerated relative to typical things. We hadn’t even raised the funds rate yet, and you were already starting to see this happening. So I think that has worked more quickly than I’ve expected. The piece that’s been, at least long, I don’t know if it’s variable, is the parts, where’s slowing the other parts of the economy.

So we did do it, and we’re still doing it. Policy remains tight. And as inflation comes down, in real interest rate terms, policy’s tightening as inflation drops. So I think there’s war coming. If that was all we had done, then I think you would say, oh, it’s all passed. All the bad stuff is passed. And so everybody’s adjusted to the tightening and nothing’s left to do. But inflation’s still high, so then we’ll have to keep tightening. And so the long and variable lags still apply. I don’t think though, and I’ll say this because I think it’s important, it would, in my judgment be a mistake to say we’ve done all we can do or we need to do and it’s all going to be working down the road, because honestly inflation’s still high, the labor market’s still very strong. We’re adding far more jobs per month than we can possibly sustain just to give the unemployment rate constant. And so that’s where you have to think about continuous tightening.

Stephen Redding:

If I could just quickly ask as well, just because it follows on very nicely to that, and then I know Jason’s after me, I just want to ask you a little bit about the labor market as well. So one of the things you mentioned in the talk and just now is that the labor market has been particularly tight. And there’s been some discussion during the aftermath of COVID about early retirements. That seems to be very small in the data, much smaller than people think. There’s also been some discussion of people sort of reservation wage rising, as during the pandemic, they saw how unpleasant it was to commute, and so on. And then in the background, there are also bigger structural shifts in the labor market as we’ve working from home and reallocation across different sectors in the economy. And so I wonder what you thought about the labor market and how the labor market’s going to play out in the coming months, and the extent to which that’s going to become a continuing pressure towards higher inflation.

Mary Daly:

So I really am beginning to think that the labor market has a, and I mentioned it in the talk, has a general shortage of workers coming back. So after the financial crisis, I was a proponent that there was more possibility in labor supply than we were penciling in. And I was very optimistic about it. And I think you have to carefully say these things, but that time I was right on my projections. Because I was optimistic that if we had the opportunity to have a sustained expansion, people would be able to come off the sidelines, and they wanted to come off the sidelines, so that worked. But I’m using that same rigor of analysis and applying it again and again, month after month to the survey data to why people aren’t coming back to work to what they’re thinking of. And I just don’t see the recovery and labor supply that we have seen in previous expansion.

So if you ask why not, here’s my leading things. Well, first of all, a lot of the loss of workers comes in the 55 plus group. And it’s not just about retirements, it’s about people not even coming back. We saw that recovery. So now the recent work that is coming out shows that we never got those workers back in, retired in COVID, but it’s actually changing the behavior now of the new cohorts coming in. So they’re just working less. So we used to have this kind of, as people were living longer and their comorbidities were lower, they were just increasing at those age groups, but you’re not seeing that, so that’s plateaued. So that’s a drag on it. We also had immigration. We had a hole in the immigration flows. We were making that back up, but we still don’t have a big boost coming from that area.

And then we have, and this is the thing you may not know, but we focus a lot on it in the San Francisco Fed, is that low and moderate wage workers, many of them who used to have two earners in the family can’t afford to do that because gas is high. It’s hard to have two cars. Childcare is in short supply and challenging to pay for. And you put those things together that basically tell a family whether it’s going to have a high rate of return to have two earners or it’s going to be costly. And that we hear a lot from those communities, that they can’t afford to have two earners. So they’re really focusing on living with what they have and managing. So that’s another hole in the labor supply equation.

So when I put all that together, I think that the imperative becomes restore price stability, get inflation down, run a sustained expansion with low inflation, 2% inflation, and you can get an economy that hopefully looks like 2019, where you have… Which was a very well functioning economy. You had people getting jobs where they wanted them, were people coming in, people with different skill levels finding opportunities to grow their career and raise their incomes. And that was an important point in the economy I’d like to return to, but there’s a lot of work to do to get there.

Stephen Redding:

Thank you Mary. And Jason’s next.

Jason:

That was a terrific talk. I wanted to ask you about the possibility and hypothesis that monetary policy has become less effective. And that’s why inflation couldn’t get up to target before the crisis. That’s why it can’t get down to target now. Maybe there’s less heavy industry, there’s less things that depend on interest rates, et cetera. So one, do you think there’s evidence that monetary policy is less effective? And two, what’s the implication of that? Is it that you need to do even more, or is it that you need help bringing inflation down, it should not just be the Fed’s responsibility, but Congress and the president also needs to play a role in bringing inflation down?

Mary Daly:

So yeah, that’s a really good question. We did ask this question, is monetary policy losing its effectiveness because there’s fewer interest sensitive sectors? And the one that was always offered to me in the pre pandemic time was we’ve replaced manufacturing with tech. And the tech industry self funds everything anyway, so how can you affect the economy? And I think that’s worth continuing to think about, but I actually really came out in the pre pandemic time with population aging, a glut of global savings, a falloff in investment because of a variety of factors, including slow productivity growth, or maybe the slow productivity growth, the result of investment. It just depends on which macro economist you talk to. But it’s just really, I think those fundamental features of the economy were doing that part of the job, they were keeping inflation low, and it was challenging to get it up to target.

Now, in the aftermath of the pandemic, I suppose I am more persuaded, and perhaps you are, by the picture I showed, the first picture that showed we started raising the policy rate and inflation’s been coming down. And there was a picture that Alan showed the grid where you see what’s happened in the first half of the year and the second half of ’22. That’s not the Fed alone. That’s also supply really coming back. But both things are working together, and as a consequence, inflation’s coming down. So I think it’s too early to say that it’s not working. The big surprise in this, frankly, is how strong the labor market’s been. But when I go out and talk to the CEOs and things, they say we had a stack of unfilled openings because there’s just huge demand for our goods and services. And so as one company wants fewer, I’m going to get more.

And so that’s something that we see going on even in the tech sector. Big companies laid people off, and medium size companies say, “Finally, I can get a worker.” So I think there’s that going on. So I don’t know that I would go so far as to say it’s not working or it’s not as effective. I think it’s too early to tell. I want to conclude. I won’t say anything about what fiscal agent should do, and I really won’t say anything about fiscal policy, but what I will say is I think there is a over rotation to have the Fed do more than we can do legally or effectively. So we have one instrument, the interest rate. And we have two goals already, full employment and price stability. That’s not a good ratio already. So if you ask us to do more things, it’s hard to do. And in the pandemic, about half of the inflation… It depends on who’s estimating it, but our estimates are about half of the inflation is supply driven, and half is demand driven. Our tools only really work on demand. They don’t work on supply.

So supply is about health and production and incentives and other things both nationally and globally. So I do think that if we want a nation that works very effectively, all agents have to participate, not just the Fed.

Audience member 2:

Thank you for a very, very excellent talk. I wonder whether there is a particular sector or what sectors of the economy that you think is or potentially will be putting the greatest pressure on inflation. Here, I’m thinking in particular of the healthcare sector, already the biggest economy, 18%, or more now. And the CBO projection projected growth of healthcare spending far exceeds GDP growth. And the demand for healthcare services and goods keep rising because the aging of the population, and the growth in the chronic burden disease, all of this. And we are short in a workforce, right? We already have lower than OECD average doctor to population and nurse to population ratios. So I wonder, with what’s coming down the pike, do you see that as a real threat to the US economy?

Mary Daly:

So I’m going to break the question into two pieces. So what sectors now am I focused on that I think aren’t already in train in terms of slowing? I showed three areas of inflation. One was goods, one was housing, and one was other services. So goods, that’s mostly supply chains, and I see that as working its way through, where it will land. And finally, it depends on that global competition piece I mentioned, but [inaudible 00:38:44] to come down. Housing, also that way. It’s an ultrasensitive sector, but it takes a long time, up to 12 months to 18 months to fully work its way through to new leases and all other kinds of things that would affect shelter inflation. So I’m really focused on this other services than housing. I think technically, we call it other services, course services x housing, but that’s not a really exciting title, so other services than housing.

And those are dominated by wage costs in terms of the firm’s bills. And so for the current period of high inflation, you’re really focused on bringing the labor market back in balance so that we can restore some stability in the wage growth path that ultimately is sustainable, and we return inflation to its goal. So on the second part of your question, so I gave four reasons why I think we could be leaning against maybe the low inflation impetus that we had prior to the pandemic. And if you did it by sector, healthcare would definitely be one of those sectors, for two reasons. First is we just… We’ve had an aging of the population issue, and entitlements that come with social security, Medicare and et cetera, just that’s been there for a while, and it just keeps…

Even though we’re not aging more, the aged are getting into that area where they are big healthcare users, and those expenditures, even if you don’t pay for him in your private sector exchanges, you’re going to pay for them in the public sector dollars because that’s just something that’s going on. And it will be something that we have to solve for or think about as a nation. The other piece though, and I think this is actually really interesting, we have an economist in San Francisco, Adam Shapiro if you want to look up his work, but he’s calculates the contribution. Many people do this, the contribution to total inflation of healthcare inflation. And what you find is in the pre pandemic area, which was very different than the decades before, healthcare inflation was falling, and so it was a drag on inflation. Now, that’s reversing and it’s going back up.

And so it’s going back to it’s like 1980, 1990 level. Well, that would be another factor that would just push inflation up. So there’s a lot of these components that look to be true for a long time, but may only have been true for that decade that was 2010 to 2019. And I think that’s one of the things we have to really think about. We can’t live on the past coincidence of low inflation and think that that’s just assume that that will go forward. So more work to be done there. But I think that’s a great question. Thank you.

I don’t think I would… So I’m going to go back to the kind of distribution that I think Jason was laying out. When I think of the talk we had last night, it’s really the modal, and then what are the risks around that? And so I will use your question to say the following thing, which is, as a policy maker, it’s important to think about the modal outlook. And your modal outlook might be different than mine, but I’m also quite focused on the risks. What’s the full distribution? And right now, I’m really worried and concerned that high inflation is eroding some of the opportunities to close wealth gaps, income gaps, other kinds of gaps because inflation is… If you even don’t have a specific study, you can point to… You can even do this with introspection. How hard is it for a low and moderate income household to substitute when the price of basic necessities rises? It’s really hard. They have lost their buffer. They are not dipping into some discretionary spending they wanted to do. They’re dipping into their real livelihoods, their ability to support their families.

I talked to about the labor market. People can’t have both earners go to work because they can’t afford to get there or have the two cars. So I guess I don’t think of it as a really rosy scenario to say that we’re doing this. What I would say is that the policy making, I’m committed, and I’ll speak for myself, I am committed as a policymaker to trying to bring the economy back to something in balance as softly as possible, because I know that that matters. And right now, the key imperative is high inflation. The labor market is strong, people are able to find jobs, but the inflation is eroding the things that actually support the future you were talking about, where wealth gaps come down and income gaps fall. I don’t see that happening right now.

Audience member 3:

Hi. Since the global financial crisis, I’ve been coming here, and the questions seem to intensify around inequality. Especially this weekend, we got a lot of questions about that. And I was wondering if the Fed considers past policies that they’ve done since then any responsibility for that? I’m not complaining. And what we’ve seen over the past couple of years is sort of a way that young people have changed the way they live, they’re not getting married at the same rate, they’re not having children, they can’t afford homes. So really, I guess to make it a monetary policy question, you have a dual mandate, part of the inflation part, do you consider affordability as something that the Fed should consider when setting monetary policy? Because you talk a lot about financial conditions. And it seems like every time the equity market rallies, that a lot of Fed speakers are out there talking about financial conditions or worrying.

So as an investor, I’m looking on saying, well, that’s code for assets are too high. We want to make things affordable, we want housing low, we want people to be able to invest in equities at the same rate that, well, we were.

Mary Daly:

Let me give you how I actually think about it, because that’s not actually how I approach this. But let me talk to talk about that. It’s a good question. I appreciate the question, but so we follow financial conditions because that’s… We raise one interest rate, the funds rate, and we want to see how it’s percolating its way through financial conditions. Because the only way monetary policy transmission works, as to Jason’s question, the only way it works is if all financial conditions get tighter, and then it bridles demand growth and the economy comes back into balance. That’s the way it works. So when I’m looking at financial conditions, I want them to be tight in the same… I want them to be as tight as the stance of policy is. And if they’re not as tight as the stance of policy, how I intend the stance of policy to be, then we have to make sure that they are. And that means more work to do, because that’s the only way we get the bridling of demand that brings things back in line with supply.

In terms of what we consider, we’re one of those institutions. Congress, we’re independent, and that independence is clearly resting on the fact that we have to stick to the goals, our congressional mandates, the things, the tools that Congress gave us and the goals that they gave us. The goals are full employment and price stability, those aggregates, and the tools are the interest rate. Now, we have ways of managing the interest rate by having different tools in our toolkit, but it’s all the same tool. It’s the interest rate. And then when we get to the zero lower bound, we used forward guidance, quantitative easing, et cetera. Those are different versions of managing the interest rate. But when you say affordability, we just don’t have the tools for that, nor do we have the mandate for that.

And you might think, well, that’s… Depends on who you are, but some people offer to me that that’s depressing. You should have those tools. And I said actually, we have one of the most fundamental things to do for the economy. Our job is to create the conditions where the other agents in the economy, including fiscal agents and private sector agents, can do the things that our society would like to see done, like narrow gaps in wealth and consumption and income and wages, narrow opportunity gaps in education and employment. But we don’t do those things directly. We just set the conditions for it. And right now, that’s one of the reasons we’re so resolute on bringing inflation down, because high inflation is not a condition for those things to happen. So restoring price, stability, getting back to that balance between people have a job and they have the sense that their basket of goods will cost roughly the same thing next month that it costs this month, that is the goal.

So I hope that answers your question, but ultimately our goals are given to us, and our tools are given to us, and that’s how we handle… Our job is to execute on those.

Stephen Redding:

Thanks very much. We’re getting tight on time, but I think there’s one last question from the gentleman in blue here in the middle.

Audience member 4:

As Jason mentioned in his speech last night, one of the paths towards a soft landing is lower corporate profit share. Some people have called for regulator Steve’s antitrust as a method for achieving that. I was wondering if you thought there’s a role for antitrust policy as a substitute or compliment to monetary policy.

Mary Daly:

So now, I get to end on something that is just the truth. I never comment on things where I have no decisional power. That is actually the way we maintain our independence as a federal reserve system, is we don’t comment on things that other agents have the direct control over. But I’m going to answer a broader question, so I’m just going to make it a broader question, and it goes back to the panel and Ricardo’s remarks, Ricardo Reese’s remarks this morning. I think it was you, Ricardo. If not, I’m sorry, whoever I messed up with, and I’m crediting Ricardo. But it really matters what… Ultimately, what’s the labor share that we are looking for? Right? So just do the other part of that. What’s the labor share? If the labor share returns to something of old 10, 15, 20 years ago, well, that’s going to have one outcome.

If it returns to just 2020, that will have a different outcome. We don’t know the answer to that. So if you want to add that, we don’t know the answer to it. That would be another factor in that four factors. I listed the four that I think are [inaudible 00:49:56], but you could put healthcare, you could put the labor share, what happens to the labor share in that. And so that’s what you have to think about. So the bottom line, the final thing, since that was the last question, is the Fed is a limited institution in what it can do, so other entities will have to also help.

Stephen Redding:

Thank you very much. Please thank me and thank you Mary for a fantastic keynote.

Mary Daly:

Thank you.

Stephen Redding:

Thanks, Mary. That’s absolutely wonderful. And let me also please thank Jason, Joyce, Allen, Bill, Ricardo, Carolyn, and Mary again for just a terrific symposium on inflation, one of the key issues of our days. Just a reminder that we have a number of exciting events coming up. We have a public talk on March.

Summary

President Daly delivers the closing keynote address at the Princeton University Griswold Center for Economic Policy Studies’ 2023 Spring Symposium: Inflation: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?

President Daly’s remarks will be livestreamed and also available as a recording after the event.

Sign up for notifications on Mary C. Daly’s speeches, remarks, and fireside chats.

About the Speaker

Mary C. Daly is president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and helps set American monetary policy as a Federal Open Market Committee participant. Since taking office in 2018, she has committed to making the SF Fed a more community-engaged bank that is transparent and responsive to the people it serves. Read Mary C. Daly’s full bio.

Related

What was the Fed’s February 2023 policy decision? And how does it affect you? FOMC Rewind breaks it down.

Ask the SF Fed: Inflation and the Economy

Watch our live discussion on Inflation and the Economy with Sylvain Leduc, EVP and Director of Research at the San Francisco Federal Reserve.

Resolute and Mindful: The Path to Price Stability

President Daly delivers the keynote address at the Orange County Business Council. She shares her latest thinking on the economy, monetary policy, the Fed’s efforts to fight inflation, and why being resolute and mindful will be critical to getting the job done.

How is the Fed working to lower inflation? The first video in our 60-Second Explainer series provides a quick review of how higher interest rates can help bring inflation down.