Transcript

The following transcript has been edited lightly for clarity.

Skip Oppenheimer:

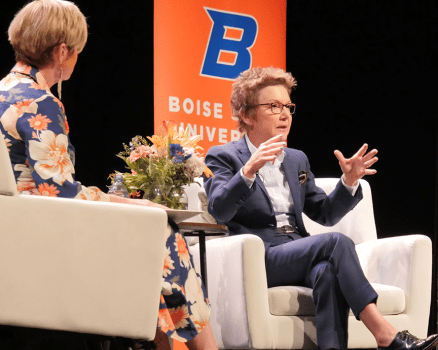

Welcome everyone. Thank you so much for joining us this afternoon. I’m Skip Oppenheimer with Oppenheimer Companies and Oppenheimer Development and have had the real privilege of serving on the San Francisco Federal Reserve Board of Directors for the last six years and was on the Salt Lake Board before that for three. I want to first of all just give a very special thank you to our partners at Boise State for hosting us all this afternoon. We were at a class earlier and one of Mary’s many, many talents is how well she connects with students and it was a really, I think, wonderful hour and a half with them. Dr. Trump unfortunately was unable to be here because she’s out of town, but I know that she very much conveyed that she wished she could have been here and wanted to be sure I sent her very best.

So I’m honored to introduce those of you who may not know Mary Daly, although she’s gotten around this city for several visits and met a remarkable number of people. But it’s my privilege to introduce Mary, the President, CEO of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank. Mary is an economist and monetary policymaker who has dedicated her career to understanding how the economy impacts people from all walks of life. And I think that’s a cornerstone of her philosophy. Mary consistently emphasizes the importance, something that I think we all agree, maybe we need more of, of listening to and learning from the people affected by economic policies. On a personal level, I will say, and as a board member, I can attest to the importance that Mary and the Fed places on gaining facts and insights from those throughout the District.

And Mary, you have set a new standard of getting out in the District and connecting in just such a personal way really with all of us in this very large western District. Mary joined the San Francisco Fed in 1996 as a labor economist and was named president in 2018. This year, she is a voting member of the FOMC, the monetary policymaking body of the Federal Reserve System. Mary holds a PhD from Syracuse University, a master’s degree from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Missouri, Kansas City. On a personal level, I will just say, and to put it very succinctly, Mary is truly one of the best and most effective leaders that I have ever worked with. And I think if you asked those of us on the board, and there’s nine of us, they would all agree.

People sometimes have asked me was there any particular surprises or if things were different when you went on the board? One thing, and I mentioned this earlier, not a surprise, really an affirmation, but I think the quality of Mary’s leadership is as high a quality as you’ll find in any institution. And the team that she leads, I just have never worked with people who have more dedication, more commitment to the work, more knowledge and just plain brainpower, but also just understanding the importance of that work and how it affects all of us throughout this country. I would just say one more thing. Mary connects with everybody, but particularly with students, and she is just remarkably good at connecting with, as I said, everybody.

But those of you who are students in the audience and those of you who were in the class saw that today. Today’s conversation will be moderated by Carolyn Holly, a very good friend. Carolyn is currently the vice president of development for Idaho Business for Education, where she has done an amazing job to further education in the state of Idaho, which is a huge passion of hers. Carolyn served for, as I think probably everybody knows, more than three decades as a distinguished on-air journalist at KTVB. She’s one of Idaho’s most experienced and best known television personalities through her sincere and in-depth approach to news and her community.

As a reminder, today’s conversation and audience Q&A is being publicly live-streamed and recorded, and we want to welcome everyone who is watching online. We will also have 15 minutes for audience questions after the moderated conversation, and we ask that you please line up at one of the microphones on each side of the room to ask questions if you have questions for Mary. With that, please join me in giving a warm welcome to Mary Daly and Carolyn Holly.

Carolyn Holly:

Well, thank you. Thank you Skip. And you probably can hear me on my microphone, I hope, at this time. There it is. Skip, that was a beautiful introduction. Thank you so much. Very dedicated Idahoan right there. So a round of applause for Mr. Skip Oppenheimer as well. And Mary, welcome to Boise, Idaho.

Mary C. Daly:

One of my favorite places to visit.

Carolyn Holly:

Ours too.

Mary C. Daly:

I land here and I feel better.

Carolyn Holly:

Yes, we love it. To everybody streaming, we are so happy to have you here as well. And to everybody in the audience, you are in for such a treat. We’re going to spend about 35 minutes in a conversation right here, but as Skip said, Mary has such a great skill of communicating with people. What I’ve noticed is that she can bring it down to the level that everyone can understand. And Mary, you’ve got a range of ages and experience in this audience and streaming as well. So are you ready to answer a few questions?

Mary C. Daly:

I’m completely ready. Now I worry that I won’t live up to the promise, but I will do my best.

Carolyn Holly:

I think you will. I really do. And don’t forget, you’re going to have a chance to ask as many questions as you can as well. So I’m going to get to some of the written questions that have come in. We’re going to start with one that I think everybody is probably interested in, which is interest rates. So you are a voting member of the Federal Open Market Committee, the body in charge of setting interest rates. That committee voted to lower interest rates by a half percentage point last month. I think it would be interesting if you could walk us through that decision.

Mary C. Daly:

Absolutely. And the thing to know about the FOMC is it’s made up of 19 people, participants in the meetings. And each of us speak for ourselves when we speak publicly and we come together and work on the statement that you see released. And then the chair’s press conference, he does a reflection of what we all came to. But today I will be speaking for myself and not representing any of the other members of the FOMC. With that, why did I fully support a 50 basis point cut in the interest rate? Let me walk you through how I thought of it. We have been, for a while now as you’ve read and known, patient to ensure that inflation is really on a path to 2%. Our number one priorities are the ones that Congress gave us.

We have two congressionally mandated goals, price stability and full employment. Price stability, we define as a 2% inflation target and we have not been achieving that over the last several years. So we have raised the interest rates to bring inflation down. And at some point as inflation started to fall, we wanted to be really confident that it was on path to get to 2%. So we were patient. At the same time, we were patient waiting for to ensure that we were confident that we were on track. The labor market, we were watching it to see is it going to be consistently outpacing the supply of workers? Will labor demand and firm’s needs outpace what we have available or will it come back to a more sustainable level?

And what we saw in the last several months, really since after the first two months of this year, is that the labor market has downshifted. It’s now at a sustainable pace of growth. We are just where I believe we need to be at full employment. Not growing too fast, not growing too slow. I am now quite confident that inflation is on path to hit our 2% goal. So that’s the economy we have today. The interest rate that we have had before we cut 50 basis points, that was elevated. And in fact the real rate of interest, which is the nominal rate minus the rate of inflation was rising. That was rising into an economy that is already nearing or at its goals. And that was ultimately a recipe in my judgment for breaking the economy for overtightening, injuring growth in the labor market and not gaining anything new on the inflation trajectory.

So the 50 basis point adjustment is simply a recalibration. We were patient, we saw that the things we were marching towards have started to evolve and we adjust 50 basis points to get policy right sized for the economy we have and the one we expect to evolve going forward. It does not mean, and anyone in the audience who thinks so, that maybe predicts what we’ll do at the next meeting. It does not. It doesn’t predict what we’ll do at the next meeting. It doesn’t tell you anything about the pace or magnitude of further adjustments. It just says that at that moment with the economy we have and the interest rate being at historically high levels, it was appropriate to take that 50 basis point adjustment to get policy in line with the economy.

Carolyn Holly:

Right. So you’re saying don’t think this is going to keep happening, but do you have any timeframe that you could offer up as far as interest rates?

Mary C. Daly:

Well, let me start with the summary of economic projections, which the FOMC puts out four times a year. So we put one out in September along with the meeting. And what you see if you look at that projection is that the median of those projections called for two more rate cuts this year, but close nearby to the median was the next level. I think there was only a percent different. It called for just one more cut this year. I think that two more cuts this year or one more cut this year really spans the range of what is likely, in my mind, given my projection for the economy. But it’s really important to put caveats with that or put the bounds on that.

Those are projections. What we are is data dependent. We will continue to watch the data, we will continue to monitor the situation in the labor market and inflation. And if things don’t evolve as we’ve projected, if we don’t continue to have a gradual decline in inflation and a labor market that stays at a sustainable pace, then we would make more or fewer adjustments. And that is what data dependence means. It means you have a projection. The projection is not a promise, it’s a projection. And as information comes in, we will adjust our projections and adjust the policy that’s right for the economy that evolves.

Carolyn Holly:

Well, what data points convinced you to cut it 50 points instead of 25?

Mary C. Daly:

Well, for me, it was really about this recalibration. So a key data point was that… You can do this if you’re a student of economics, you’re interested in this. You could just look at the nominal rate of interest at this really tight levels by history, really tight policy. And then you could look at the real rate of interest by plotting inflation a year ahead, inflation expectations against the interest rate. And what you see is that real rate was rising into an economy where inflation is getting near 2% and the labor market, I do not want to see further slowing in the labor market. I don’t want to go past this sustainable pace of growth. And you put those two things together and it’s just an adjustment in policy.

Carolyn Holly:

All right, we’ll be looking for those things. Thank you so much. You are a labor economist by training.

Mary C. Daly:

I am.

Carolyn Holly:

You’re a lot of things, but economist by training, labor economist. Can you give us your overview of the labor market right now? You talked a little bit about it at the beginning of your response to the question, but give us your overview of the labor market.

Mary C. Daly:

So I see the labor market is… And I had a great question from my student meeting just a little bit ago on the labor market, but let me talk to you a little bit about how I’m thinking about the labor market. So right now, and you see this if you’re in Boise or anywhere else. I have nine states in the Western United States that are part of the 12th District. So that’s all the inner mountain states, all the coastal states on the west, and then Alaska and Hawaii. Wherever I go, I see a labor market that is more balanced, where firms say… And we just met with our councils and boards last week, and everyone who we met with said, “Yeah, the labor market, if you’re an employer is more balanced.” We have more applicants applying for our jobs.

We’re able to retain workers who join our firm more easily. We can invest and provide resources, and we are able to reduce that churn that was coming through when the labor market was very, very hot. So that’s a good sign. On the worker side though, there’s two sides to the labor market equation. Always. On the worker side, we’re hearing that individuals can still find jobs and that they’re able to use their skills to get the jobs that they want, but it might be taking a little longer and you might get fewer offers for your search than you used to. And that’s a labor market that’s more in balance. A simple statistic that I like to look at that I find very useful is what we call the vacancy to unemployed ratio.

That’s just the number of postings nationally across the United States against the number of people searching for work. At the peak of the tightness, it was two vacancies for every one person searching for work nationally. Now it’s one vacancy for every person searching for work. And so you can imagine that takes longer to find the match between the firm and the worker, but that is a labor market that’s more or less in balance.

Carolyn Holly:

And do you have any thoughts on, we have a lot of employers who want employees to return to work, who’ve been off or working remotely?

Mary C. Daly:

Yes, absolutely.

Carolyn Holly:

Especially with Covid and everything else. Do you have any thoughts on how that’s going to affect the labor market?

Mary C. Daly:

Well, this is an evolving situation. And I remember coming out of the pandemic and commentators mostly would proclaim that nobody’s ever going to go to work again. And they also said that women wouldn’t come back into the labor force, they would stay at home after that, but none of those things had happened. What you see is that people are coming back into the office. Hybrid is becoming the dominant model. I think it’s highly unlikely that we’re going to find ourselves back on a five-day work week in the majority of firms.

I know some firms have announced that that’s what they are going to have, but for most firms, what I’m hearing and seeing is that it’s really a hybrid situation where it’s two to three days a week in the office and it’s flex time on the other side. And I think that strikes a nice compromise for the labor market where people can have the flexibility they want and need to do things for their families and participate in their communities. And it gives employers what they really, really want, what they know is their magic. The magic fabric or glue of an organization is its culture. And it’s very hard to create a durable culture when you’re completely remote, especially if you’re not used to being completely remote. And I also think that employers are recognizing something that at the Fed, San Francisco Fed, we’ve recognized early on, is it’s very challenging to integrate younger workers or newer workers to your organization if they never see anybody except on Zoom. So being in person has benefits and having flexibility has benefits, and that hybrid is the way that you can get those things. So that’s how I see most firms, that most firms are gravitating towards that when they have the ability to do so.

In terms of productivity and job retention, we are tracking that productivity hasn’t really changed very much because the hybrid seems to work well. Firms can find flexibility and it enhances their productivity. And in-person time does as well. And then, what we do know is that when the labor market is more in balance, firms get a little of what they need, workers get a little of what they need. Nobody wins the battle completely. And by a labor economist definition, that’s the definition of balanced.

Carolyn Holly:

Yep. You got the answer to that one then. I’m sure everybody in their mind is thinking about it, whether a business owner or not. All right. You do a lot of traveling around your District and talking to a lot of people. What are you hearing from people and businesses across the District and then here in Idaho as well? Because spent today talking with a lot of people. What are you hearing as they do try to navigate the current economy?

Mary C. Daly:

So here’s what I’m hearing, and it’s remarkably similar across the country, not just in the 12th District, and I do do a lot of traveling. I feel like one of the most important aspects of data collection is to talk with individuals who are actually living in the economy and asking them, and that’s called qualitative data collection. You just don’t look at the headline numbers that come out and get printed in the newspapers or on the media. You have to talk to people to see how they’re doing.

Here’s what I’m hearing, cautious optimism. The economy is progressing and people understand that. When I ask questions like, “Are you expanding?” “Well, we’re picky about where we expand, but yes, if it looks profitable, we’re expanding.” I ask questions about, “Are you finding skilled workers that can do the jobs?” “Yes.” When I talk to workers, “Do you see opportunities for career mobility?” “Yes.”

So that’s an economy that people feel optimistic about, so why add cautious? Because we talked about this a little bit again in the student conversation. I think people feel a little precarious right now. And I think that feeling precarious is also about the uncertainty, right? How will we get from high inflation to this proverbial soft landing, and more importantly, beyond? So it’s not just about bringing inflation down, it’s how do we get to a durable expansion? And where do I fit into that durable expansion?

And when you’ve been under a high interest rate environment and high inflation for a while and you’re coming down, you get excited and optimistic. But then you still realize that we’re not quite there yet. Victory is not ours yet and we have to keep working. And I think that the closer we get to people feeling like they don’t have to think about inflation and the economy continues to expand and they continue to be able to get jobs and grow their businesses, I think that gives people the relief they need. So the best remedy for uncertainty is effort and work, and that’s what we’re up to.

Carolyn Holly:

Right. But as you say, the consumer is in it for me, that type of thing. Do you ever think we’ll see prices go back down on food on gas?

Mary C. Daly:

That’s a great question. That’s a great question. Prices of individual items can fluctuate, especially for gas and other things and food. But in general, what people are wanting, and I get it, is well, it’s not really 2019 because the price of things that I buy is higher than it was in 2019. And that’s what inflation has done. It moves the prices up. And the Fed’s job is not to move the prices back down, it’s to bring the growth rate of prices to 2%.

So a young man wisely asked me, not here, this is about a year ago, “Well, if you just bring the growth of prices to 2%, and the price of eggs is three times what it once was, it’s still higher for me. Right?’ And I’m like, “Yes.” So he said, “Well, how do we get out of that?”

And so, this gives me an opportunity to say a little bit about how the economy historically works and how I think it will work this time, is that you get through a bout of high inflation, which everyone understands is a tax on their wellbeing and their end, especially for those least able to bear it. So what happens, and has started happening in the middle of last year, is wages started to outpace inflation. So for a lot of the high inflation period, wages were not keeping up with inflation and real wages were falling. But in the middle of last year, across the nation, the average across the nation, real wages started to grow. Well, as real wages grow and they grow over time, then a price that is higher than 2019 doesn’t feel as challenging because your wages are much higher than 2019, and you’ve caught up basically. So you’ve caught up so that you don’t feel like your wellbeing has been taxed. You recognize everything just kind of shifted up.

But why people feel so challenged right now is because prices shifted up by more than earnings. And we have to let earnings get to that place. And that’s why we keep talking about getting inflation to 2% without injuring the economy. Why we don’t want to see further slowing in the labor market because people need their labor earnings, they need the economy. Businesses need their profits in order to feel like they’ve been made whole.

Carolyn Holly:

How much of that is the mindset?

Mary C. Daly:

Well, I think some of it is mindset, but I think there is a real pain to this. And I watched my parents, and this is not in this past in high inflation, we’re going to go all the way back. So in the 70s inflation, I was young, and I watched my parents and everybody in our neighborhood struggle with high inflation. And it was not just a mindset, it was real, right? They had their income and then inflation eroded that and then suddenly they could pay for fewer and fewer things. And that creates a lot of stress. And I saw some of that same stress in the faces of people we interact with in this period of high inflation.

And what I remember from that period is that we were in a very different world, one we luckily never got into this time around. We were in a world where in order to get inflation down, the economy really had to slow. And that was the, for those in econ, it’s Volcker disinflation. For those who remember it, it was the Volcker disinflation. It was challenging because so many people lost a job in a recession. We have not had that experience here. And what that allows is for us to reduce inflation, let earnings and incomes and employment and the economy grow and have people feel whole.

So I think it’s much more than a mindset. I think the pain is real. I think the sense that you’re on a treadmill that you’re not winning against is real. And so, that durable expansion that allows that equation to balance back out, that’s why I’m so committed to both sides of the mandate. It’s not only Congress gave us those goals, which it did, and so we obviously hold to those, but because it really is the equation people want. They want both things, low inflation and full employment.

Carolyn Holly:

We’ve got a lot of students out here. You’re at a university and I know that you are such a proponent of education. If they want to make a livable wage, what would be your advice right now?

Mary C. Daly:

Invest in yourselves. I think this is the most important thing. So first of all, I’ve met just a few of the students, but I love them. In Boise here, you have a tremendous group of students. I meet students everywhere I go. These students are engaged, excited. I got some of the best questions I’ve been asked at the econ meeting we had, just terrific. So this is our future and we should be proud of it.

In terms of a living wage, I think that we talked about this a little bit in the previous meeting, but it’s something that is important, is if you invest in yourself, then you have the opportunity to move around however the economy evolves, right? The economy will evolve. I have been through so many evolutions of the economy in my career. What I’ve learned is in my skills and abilities, I can move around. I trained as a labor economist in microeconomics, and I work at a macro institution doing monetary policy. And I could move around because I had that investment in myself that allowed me to say, “Okay, this is just another part of the economics puzzle. I can go there.” And I think that’s the piece about it.

I was just also this morning at the College of Western Idaho, and whether you’re learning a trade or you’re investing in a four-year degree, the most important thing is you can find a place in the economy if you’ve invested in skills and strengths that sort of put you into this ladder. And then, you just have to continue to live and be a lifelong learner. I gave this thing out to the students today about being curious, be confident, be humble. And I think that voracious curiosity to always learn is what kind of fuels people to continue to make a wage.

And then, the economy is not just about what the Fed does. We play a role, but it’s also about what our businesses do. And I think businesses don’t get enough of a shout-out. Sometimes people are like, “Well, businesses, what are they doing?” And I’m like, “Businesses are fueling our economy.” So when you see a small business owner, a medium-sized business, or even a large business owner, they’re the dynamic of the economy that along with all of us create community.

Carolyn Holly:

And they invest in themselves by investing in their employees as well.

Mary C. Daly:

Absolutely.

Carolyn Holly:

Yeah.

Mary C. Daly:

Absolutely.

Carolyn Holly:

You’re right. Okay, A couple of things that are really kind of special to Idaho. And the first one is, we have had heck of a wildfires, not just in Idaho, but throughout the West. And I believe there’s been some studies done about how wildfires are affecting the economy. Can you share some of that with everybody?

Mary C. Daly:

Absolutely. So this is actually not a new issue. It’s just one that’s increasing in everyone’s understanding of it because the frequency and magnitude of severe weather and drought and wildfires, and we have just now two back-to-back hurricanes in the Southeast. These are a lot of natural disasters all at once that have changed not only how people are living in that small geography, but I think a greater awareness of the fact that weather and these kinds of disasters can disrupt your lives.

And so, researchers, whether they’re at universities or in the San Francisco Fed or other Federal Reserves, at the Federal Reserve, we don’t have any role to play in climate policy or weather policy or how to think about helping with natural disasters. But what we do have to do is understand how whatever’s going on in the world is affecting the economy.

And what we see when we do those studies is that, and you hear it if you read the news or listen to the news, is that at this point, insurers are wondering about where they’ll insure. Financial institutions are wondering about where they’ll lend or how much they’ll charge, depending on if it’s located in enough fire-prone zone or a hurricane-prone zone.

There’s a lot of extra business costs that are incurred when you open a business because you have to think about, “Okay, what happens if this?” And also, there’s a lot more attention to resiliency management, which you can do if you’re a larger firm or medium-sized firm about locating your work in different places. But if you’re an ag-based institution, even number of days that are really, really hot or smoke-filled. It’s not just whether you’re near the fire, as you all know here in Boise this summer. The number of smoky days has been very large, and that means less outdoor activities. But it also means less ability for workforces to be outside, work in healthy environments and do that work. So I think all of those things, the research is saying that we don’t know how it will end up, but it is changing the cost structure of how businesses think about it.

Now, what I’m very encouraged by is that businesses are thinking about this and banks are thinking about this. And from an economics perspective, you want businesses, communities, and banks to think about this so that they can manage the risks before us. But I see this across the country that this is happening.

Carolyn Holly:

Yeah. And it’s really changing because it wasn’t happening before.

Mary C. Daly:

It’s completely changing. It’s completely changing.

Carolyn Holly:

Doing some research—

Mary C. Daly:

It’s a great question, by the way.

Carolyn Holly:

Yeah, thank you. Doing some research with you, I think it’d be wonderful if you shared with this group and also streaming it right here, your work, the San Francisco Federal Reserve’s work in our rural communities. We think it’s just everything that’s going to affect the city and that type of thing. But you’re doing some great stuff for outside of city living.

Mary C. Daly:

Well, the important thing, whether you’re a central banker or anybody in the economy, but as a central bank policymaker, it is essential that we think of everyone in the economy, right? The economy is about people, and everyone matters in the economy. And it’s not just an urban-focused environment, so you have to go out in the rural community. So we had a rural economic summit over here in Eastern Idaho. We’ve done work across the District in rural areas. But the work we’ve done is really in a discovery mode. What can those local economies, what do they need? What kind of businesses can grow there and support there? What kind of training and workforce development is needed?

And we don’t have a role in creating any of those things. We have very narrow mandates. We have three functions that the Fed: monetary policy, the financial stability, financial institution, safety, and soundness, and the payment system. But what we do know is we can convene, bring voices together, bring good research, help people connect to each other to learn.

And what I’ve learned is there’s a lot of interest in rural areas in transitioning to a more diversified economy. But the equation doesn’t always pencil out for the traditional way of business development where you just get a big business to move there. It’s really about growing it from the ground up. And it starts in many ways with education and skill development.

I was encouraged by, there’s Idaho Businesses for Education, there’s Within Reach, which we help with on that, facilitate that here in Idaho. That’s a model we can use in other states. And there’s also just this renewed interest in recognizing, and I think this is really something I see in Idaho, Utah, other Intermountain states, but I think Idaho and Utah lead the way in the 12th District, of everyone in the distribution of interest really matters. So four-year degrees matter, two-year degrees matter, certificates matter, lifelong education matters, because we have a lot of work and we need skilled people in all of it. So I think that’s something the rural areas are latching onto and saying, “Oh, we don’t have to get … ” there’s only so many four-year college graduate in business administration jobs you can find in a rural area, but you can find a lot of jobs in other parts of that interest distribution. Thinking about how we populate that is something that’s important.

Carolyn Holly:

Yeah. We need the engineers who are going to work on the tractors.

Mary C. Daly:

Yeah. You need people who are interested in that.

Carolyn Holly:

Yeah, so we can continue to grow our food here.

Mary C. Daly:

Or you mentioned weather. Thinking about how you can grow crops in different conditions than you were growing in before. I mean, you’ve had other weather challenges before. It’s not just you’ve never been challenged by weather in Idaho, but this is just new challenges. We’re very adaptive as people, and I think getting the right talent to the right place and saying, “Here’s the challenge, how do you fix it,” they’re going to find a way.

Carolyn Holly:

Isn’t she cool? You guys having a good time? Let us hear from you, as we get a temperature check of you out there.

Mary C. Daly:

I can’t see any of you because it darkens you.

Carolyn Holly:

I know. It’s real dark.

Mary C. Daly:

I have no idea.

Carolyn Holly:

We can’t see any of your faces.

Mary C. Daly:

You could be writing evil notes and holding them up to us, and we would have no idea.

Carolyn Holly:

The reason I say that is because I want you to get ready with your questions, okay? Mary is very willing to take your questions. I want you to know we’re publicly streaming, so you know that. Microphones are on each side. Do not be shy, and do not miss this opportunity to ask Mary a question, but I’ve got another one for you.

Mary C. Daly:

Okay, I’m ready.

Carolyn Holly:

It’s Idaho-centric as well. “What kind of opportunities do you see for Boise and for Idaho’s economy moving forward?”

Mary C. Daly:

Well, in the scheme of who needs opportunities, it’s not you all. You guys, this is a growing economy. Really every time I come, new things happen. I was touring around with Skip and others and I’m like, “What’s that? What’s this? Why is that crane there?” It’s really remarkable how dynamic Boise has become. When I started coming to Boise in 1996, it was this, and now it’s this. People say Boise, and they mean a lot of things beyond just Downtown Boise, so that’s remarkable.

I think the opportunity that I see … and this is a real opportunity that I think about … is there’s a problem that we’ve tried to solve historically in the United States, that we transition from one kind of industry to another and people get left behind. Agriculture’s an example. People transition off the family farms because larger farms come in, but they want to stay in those areas, and then what do they do? This is a place, I think Idaho is a place, where you can think about, well, what do we do? How do we diversify our whole economy, not just the urban centers of the economy?

How do we make every part of our state dynamic, and what are the parts of the infrastructure we need? That’s partly education. It’s partly investment. It’s a lot of public-private partnerships. I see that as the real opportunity, to say, “Okay, how can we model what great looks like as we think about all of our citizens, not just those in urban areas?” I know this is top of mind for civic leaders, but it’s something that we don’t have a model that I could just pull off a shelf and say, “Okay, you can do this.” I think there’s leadership roles that you can play there.

I also think that there’s a unique challenge in this moment in our history of housing. No one has solved the housing issue. Not a single state, not a single locality. In fact, there’s a survey by the Cato Institute. It asks this question, “Are you worried about housing,” and 85% of Americans, 85, said they were worried. That was true whether they were older or younger or middle. That was true no matter what their education level, no matter where they lived in the country, no matter what political affiliation they had, no matter what race or gender they were.

Everybody’s worried about the cost of housing, and the gap between demand for housing and supply of housing is now very large. I think localities that are already built on community are going to have to think about how do we solve that problem, and then we’re going to have to borrow from each other to say, “How do we scale those solutions?”

Carolyn Holly:

Yeah. Keep shoutin’ about it, okay, and keep making sure that everyone realizes that you gotta think of everybody, as you said, when it comes to those conversations.

Mary C. Daly:

Everybody.

Carolyn Holly:

I want you to think. Do we have people that are coming up to the microphones? You may not be able to see them because the lights are pretty low here, but we are starting. We’ll take your questions.

Mary C. Daly:

Yay. Now I can see those eyes.

Carolyn Holly:

I even had a question in my back pocket if no one would stay there. Do you want me to just ask it real quick? As I’m waiting for people to go to both microphones, Mary, tell anybody here, what are you reading right now? What would you recommend for a good book right now?

Mary C. Daly:

Oh, okay. I’m reading this. I love mysteries, and every time I get off of this guy, this mystery author, I get back on, because I love reading about where he works. It’s C.J. Box, and he writes these mysteries. He’s a park ranger, a wildlife ranger, and he’s writing these mysteries about places. Every time I get … I’m not doing an advertisement for him by the way … but I read these books that I say, “I’m not going to read that for a while, I’m going to read something else,” and then back to my Kindle I go to look for a new one. That’s what I’m reading.

Also I’m trying to learn to do different things, including … and you might ask yourself, “Why does she take up hard things at different ages?” I took up golf in the pandemic, and so now I’m reading a 450-page book on how to get better at golf.

Carolyn Holly:

I think we have a few people out here who could talk about your swing maybe.

Mary C. Daly:

Yeah, and so I’m just like, “Okay, whatever. I’ve nerded out.” I’m bringing my economist wisdom to golf, but then when I get on the golf course, I just try to be an athlete. I did get associated it with it during the pandemic, and I’m enjoying it.

Carolyn Holly:

Excellent. A little bit about Mary’s personal life. You arrived first at the microphone. Please identify yourself and ask the question.

Chris Sivaggio:

Sure. I’m Chris Sivaggio. I’m retired here in Boise, Idaho, and you just brought up the question I was going to ask you. It’s around shelter costs. As you know, we’re at an all-time high with shelter costs, and it includes taxes, insurance. As the Fed starts driving interest rates down, has there been any modeling or concerns that that will increase the affordability, but it could also be a little bit stimulative to demand because there’s pent-up demand in the housing market right now, and it could cause prices to increase in that place? The impact of the lower interest rate may be minimized, at least in shelter costs, because of where we are in our housing experience.

Then secondly, as right now the Affordability Index and first-time homebuyers, really a lot of them are priced out of the market, is there a solution other than lower interest rates, or do you think it’s going to take four, five, six years for wages to catch up and make it more affordable eventually, so first-time homebuyers can get back in the market?

Mary C. Daly:

Let me start with that question. I gave a speech up at Portland at a community development conference in March, I believe, and I talked specifically about housing. We did a lot of work to put together some facts that would, I think, resonate, right? We know the housing narrative, but what are some facts that would resonate? I made a simple plot of housing demand and housing supply, by new household formations against the new units coming into the supply network for housing across the country.

The first thing you learn when you make this plot is that this is not a new problem. This is an old problem, right? This is a problem that predated the pandemic. It was something that we already knew was happening. It started after the financial crisis. After the financial crisis, a lot of housing developers got burned. A lot of developers pulled back and they said, “We’re not going to overbuild, so we’re going to build slowly.” Household formations were coming, and that gap emerged. Now it’s gotten much worse because just time takes it further, and then we had a pandemic, and then we had high inflation and high interest rates, and so builders weren’t in the game.

What happens when we lower interest rates is two things that have an impact on housing markets that is positive. The first thing is that one of the reasons, and that’s been part of the reason that there’s no housing supply on the market and people couldn’t trade up, is because they were locked into low mortgages. If you’ve got a 3% mortgage rate and mortgage rates were at 7%, you didn’t really want to move up, even if you’ve got your whole growing family living in a small starter home. There were no starter homes available, because all the people who started in those homes now don’t want to move. As the interest rate goes down, that pipeline will open up. Individuals will move out. They’ll go to new houses themselves, and then starter homes will become more available.

The second thing that has happened, as soon as we did the FOMC announcement in July where we said that our price stability and full employment goals were roughly in balance, and the Chair subsequently communicated that the direction of change for interest rates was likely to be down, what happened immediately is homebuilders who were shovel-ready, but they were sidelined because of the high interest rates, they started getting into the game.

When we did our contact calls and our CEO roundtables with housing, what we learned is homebuilders are getting back in the game. Now, they’re not diving back into the game, but they’re bringing shovel-ready projects back in. Why? Because they know the direction of change for interest rates is down. Those are two pressure valves that will help housing supply.

The real thing … and I’ll leave with this … that is important is that, if you look back in the … don’t write these down and quote them. You’ll get the gist and then you can fact-check it in my speech, because that’s where I would go to fact-check it. You can look if you were curious, but it’s something roughly like this. If you look back into the late ’60s, over 50% of homes available were affordable to the first-time homebuyer. That number has plummeted to 13%, and is now probably lower. That’s over a huge time span, and it’s not about the Fed or the economy or the pandemic or any particular program. It’s about just what is the dynamic of building and how do we think about that.

That’s why I’ve offered that it’s probably going to take the public sector coming in and saying, “Okay, what about our zoning? What about our rules and regulations?” It’s going to take the private sector saying, “Well, what are we building across these dimensions?” It’s going to take the workforce saying, “Okay, how do we see a ladder going?” Where there are communities that are making a dent, it’s really because of those public-private partnerships, and firms’ recognition that you can’t really have a reliable workforce if they don’t have a place to live.

I’m not very worried about us re-accelerating inflation by lowering the interest rate. I was more worried about us injuring the growth and labor market of the economy if we held policy too long. We’ll always watch the inflation data, and if they come in differently than we’ve projected, then we will absolutely respond to those data.

Chris Sivaggio:

Thank you.

Carolyn Holly:

Thank you for your question. Over here.

Skip Oppenheimer:

Thank you. Welcome back to Boise.

Mary C. Daly:

Glad to be here.

Skip Oppenheimer:

Thank you for your insights, and thank you for taking my question. This is going to carbon-date me, but 43 years ago I was sitting on a trading desk in Wall Street, and I was trading the 14s of 11, which was the 30-year bond at the time. It had a 14% coupon. Pretty amazing stuff, because it’s got 4% now. I want to ask you a specific question relating to the Fed’s balance sheet and how that might have affected the inflation that we’ve just come through, which is the highest we’ve seen in 43 years. The balance sheet has roughly … it’s actually gone up 125% in the last four years, so I think it’s around 7 trillion now … but it hit almost $9 trillion.

I’m curious as to getting your thoughts as to whether the balance sheet, the expansion of the balance sheet, had a lot to do with us hitting that inflationary mark. I know it has a lot to do with bank loans and things like that, but I want to hear your insights about that, and how can you get comfortable with the idea of inflation residing back in your 2% range with a balance sheet that’s still $7 trillion, and it seems to be stabilizing there, but it’s a huge monetary expansion? I’m curious to get your thoughts about that, and what you think inflation is going to do going forward. Thank you.

Mary C. Daly:

Absolutely. The idea that inflation might be being affected by our balance sheet policy first arose after the financial crisis when we also used our balance sheet tool, and people were worried. There was a lot of concern that maybe that would boost inflation. There’s been a considerable amount of research on the balance sheet and inflation, and there’s very little evidence that’s been mounted that would suggest that it has much of a direct effect.

Then the question that I would look at is, well, what do we see happening right now? Well, first thing that happened that I see is that we can trace inflation’s roots back to two things. The fact that when, in the pandemic, supply chains really were injured. I mean, it was tremendous how much global supply chains got disrupted. I don’t think anyone really would’ve predicted such fragility and such challenges in bringing them back, so that was piece one.

Piece two was the restraint on demand that a pandemic creates wasn’t as large as I think people might’ve expected because people went home. If you’re on-site essential workers, you’re there. If you’re unemployed workers, you got laid off, you got benefits and support, and if you were working at home but still working, you were getting paid.

All of that income is there from all those different sources. People had online shopping and online things, so they just kept spending on things. One was just to retool their homes so they could actually do the work at home, but then there’s just this idea. I mean, consumer spending was amazingly strong, especially coming out of the three months after we were mostly locked down, so demand just surged. People went back out. They bought things. They were well supported by the three things that I mentioned. You’re working at home, but you don’t have any place to go, so you accumulate a lot of savings. If you’re unemployed, you’re getting some support, and if you’re an on-site essential, you’re working.

You’re just getting all of that happening. A real surge in demand, a post-pandemic surge … well, post-lockdown surge in demand … was met by a very restricted supply. What looked to be a temporary disruption between those two became a much more persistent disruption because supply chains just took a long time, over a year and a half, to recover, and demand just kept going up. Those two things were the key drivers to inflation and why inflation’s fallen so much. Even while the balance sheet is… The balance sheet is coming down to more normal levels, normalized levels, it does grow with the economy. So you can do it against some metric like percent of GDP or something like that to sort of normalize it, but it went rose and we’re normalizing it now, bringing it back down to what we want for an ample reserves regime, which is the regime we run, and there we are… But what we see is that all of that’s been happening and inflation’s been coming down.

So I think that’s just another point for me that it’s really not directly infecting inflation, it’s really about inflation’s being driven by things on the real side of the economy, which is the supply and demand imbalance. As the supply chains have recovered and demand has come down because of a higher policy rate, tighter monetary policy, you’ve seen the economy come back into balance and now we’re coming in near our target. We’re not there yet. I want to remind everybody, we’re not there yet. We are not satisfied with inflation that’s above 2%. So no victory declaring here, but we are definitely moving in the right direction. So that’s how I think about it as I unpack that.

Carolyn Holly:

Thank you so much. Let’s get to as many questions as we can. Go ahead.

Jack Burnett:

Hi, my name is Jack Burnett. I’m an accounting and finance student here. I’d love for you to shed some light on how does the Federal Reserve try to hold the dual mandate of maximizing employment and maintaining stable inflation while also addressing the growing concerns around economic inequality here in the U.S.

Mary C. Daly:

So the Federal Reserve doesn’t have a direct role in inequality, but it is a great question and in fact it’s a question that I felt was so important, I gave a speech in I think 2020, but I can’t remember. We could send it to you if you’d like, but the reason I’m saying is not to say here’s my great speech, but I really took this seriously and I think the title is even is the Fed Contributing to Inequality, and what I did then is I walked down, I’ve been a long time researcher in income and wage and employment inequality, and I looked down the list of what happens when the Fed’s policy changes.

And what you see, and it’s just a fact, is that when we have price stability and full employment and a sustained expansion, take the eleven-year expansion that only ended with a pandemic that came in 2010 to 2008 to 2019, what you saw was gaps closed, employment gaps closed, consumption gaps closed, wage gaps closed, income gaps closed. Wealth gaps started to close at the very end.

But what often happens is when the economy’s going strong, stock markets go up and the gaps close at these other levels. But if you don’t have access to housing or stocks, then you’re not gaining in the wealth accumulation that takes place. So the Fed doesn’t have a role in that. We don’t get to decide who has a stock or a house and who doesn’t. So what we can do is really simple. We can create, as our congressional mandates asked, we can create the conditions where other things are possible and the conditions we’re meant to create by our mandated goals are price stability and full employment. So when we do those things, we’re setting a foundation that allows other good things to take place.

Carolyn Holly:

Thank you. Yes.

Audience Member 1:

Thank you for being here. I was just wondering how do you personally make decisions and look at resources that you have at your disposal without political affiliation or decisions, like looking at the facts and believing in what you believe in and not what everyone else wants you to? Thank you.

Mary C. Daly:

That’s a great question. So the Fed is apolitical and we are independent by our creation in 1913, and that is a responsibility that we take seriously and we recognize, I recognize personally again and again that the only way to keep that true and live up to that expectation is to have integrity. Because integrity builds trust and trust gives people confidence and comfort that we are doing the job that we were asked to do. So it’s just easy to hold on to. Right when I became president, I put up a poster in the front of our lobby, right as the employees and the public walks in and it says what is true. Our work serves every American and countless global citizens because we are a global economy and the U.S. is a trading partner for so many, so our work serves all of those people.

If you walk into the bank and it’s like a touchstone and that’s your mission, that’s your purpose, well, then you can’t let anything else detract you. So we keep our heads down at the Fed, we focus on what is given to us, and we know that by doing that we are serving the people who we work for. Because ultimately, and I tell my team this all the time, we work for all of you. I mean, you’re our bosses, you’re the people we do things for. If you weren’t here, we’d have no jobs or role to play. So I take that so seriously, that political things would never weigh in, and there’s plenty of facts and evidence and models, and then I use that mantra that I gave to the students earlier today. I’m voraciously curious, try to learn everything I can, especially from those who don’t agree with me.

I’m confident when I go in to make a decision because I know I’ve done everything I can and then immediately after making the decision, I have to have humility. You have to be humble. So curious, confident, humble. If you do those things, you stay focused on mission and purpose, then we can accomplish the job.

Carolyn Holly:

Great question. Next one. Oh, wait.

Mary C. Daly:

I’m supposed to go over there.

Carolyn Holly:

There we go. Over here. I didn’t see anybody over there.

Audience Member 2:

Hi, how are you doing?

Mary C. Daly:

I’m good. Thank you.

Audience Member 2:

Okay. Sorry, my question is to you is, so how does the Federal Reserve take into account state legislation that usually hurts a state’s economy, kind of like the new California 20 an hour minimum wage law. But my actual question is how the Fed takes those laws into consideration and when deciding rate cuts.

Mary C. Daly:

The first thing in that is we make national policy. Our policy decisions aren’t made for a particular state or region or particular sector of the economy. We’re really making policy for the nation to achieve those two goals. The state and local policies or even national policies are all part of what affects the economy, and so we’re monitoring the impact on the economy of things, but they’re very aggregated. It’s like that would be, if you think about different wage floors, that would be a wage floor. And if you think of a wage floor, which is not just in California, but other places have put in wage floors, that just raises the cost for employers. And when we talk to employers, if they tell us it’s a material thing that they’re changing how they produce because of, we would know that, but we wouldn’t be reacting to the law or projecting what that’s going to do to the economy.

We’re really talking to our employers and our workers groups and our community groups to see how it’s impacting their economies because so many things go in to a decision of a firm or worker about a job or where to locate your business or how to think about growing your business. All of those things… Whether to invest in technology, all of those things matter, and it’s really something that’s important because as an economist, I have a lot of research I could talk to about how all of this should work and shouldn’t work, but that’s not my role. My role is to use economics to think about things, but my role as a policymaker is to make those decisions at this level and not project or comment on things that are really up to our elected officials and not me.

Carolyn Holly:

Thank you.

Mary C. Daly:

Okay.

Adam Metrim:

I’m Adam Metrim. I’m a student here and an intern at the city of Boise. And you kind of touched on housing supply earlier. I’m curious, what are the Fed’s strategies to ensure that with development ramping up and developers getting more confidence, how does the Fed ensure that the environment has room for affordable housing projects to pencil out and not just the environment dominated by luxury housing right now?

Mary C. Daly:

We don’t have any role to play in that. I mean, this is the thing that’s always dissatisfying when I go and people were like, “Well, could you do this? Could you do that?” And we really have three responsibilities, monetary policy, the payment system, and then financial safety and soundness of the financial institution. In monetary policy, we have one tool, the interest rate, and we have two goals, those two that I mentioned.

And so we do have something called the Community Reinvestment Act that encourages or regulates how banks have to participate in affordable components. It’s a complicated rule, so I can’t explain it all here, but it does give banks the incentives and the parameters with which they have to make investments in their communities. But I think you’re talking about something much larger than that because the CRA has been in place for a long time. We still have an affordability issue.

I would say that as I answered the gentleman over there, the affordability issue, I always try to get people to stop talking about… And I really want to be careful here. I think we’ve talked so much about affordable housing that people think we mean housing for people who can’t… That are at the bottom and can’t afford housing. That is a very different thing than what we’re facing as a nation. We’re facing missing housing up and down the housing distribution, up and down the income distribution. I mean, we’re to a place now, especially according to this Cato survey where if you grew up in a location, say, let’s take Boise Idaho, your family grew up here, you’re going to start a family. Your parents want you to live near them to have grandkids nearby or something, and it’s affordable, it’s hard to afford that, right?

It’s just really challenging. So I think we should expand our definition of affordable and realize that the workforce up and down, the income distribution needs a place to live. But also communities need people of all types to live in them, to thrive. And I think that’s what I’m seeing public civic leaders trying to do along with private sector developers.

Carolyn Holly:

We have people lined up here, but Mary, we’re running out of time right here. Do you want me to take one more?

Mary C. Daly:

Do you have a speed question?

Carolyn Holly:

Question?

Mary C. Daly:

I’ll give you a speed answer.

Carolyn Holly:

Speed question. Nope. Speed question.

Audience Member 3:

Hello. Thank you for your speech today. My question is on fiscal policy and how it relates to monetary policy. Chairman Powell recently indicated that our country’s on an unsustainable fiscal policy path and we have debt 120% of GDP, servicing that debt now exceeds the defense budget, and then we have all these unfunded liabilities that can dwarf that. Neither political party seems to care about this. And so my question is twofold. One, is this something we should care about? And secondly, what are the implications for monetary policy of continuing on this path?

Mary C. Daly:

So fiscal and monetary policy, we don’t really work in together. The fiscal agents or elected officials take policies for our country. We at the Fed work with the economy we have, so after the fiscal agents have decided what they want to do and how that evolves, we work with the economy against those two goals I gave you. In terms of should we all care about our fiscal sustainability as a nation, I think that really we should, and I think we do. And so I’ll leave it at that. We should and we do, but that is something that’s not part of the Fed. So when I say we should and we do, I say that as a citizen and not as a policymaker because the Fed plays no role in that.

Carolyn Holly:

Thank you. We are wrapping it up here, but I really wanted to give you, Mary, 30 seconds to any final words that you’d like to say because there’s been an array of questions and very good answers as well. 30 seconds to wrap it up for us.

Mary C. Daly:

So boy, it’s like a final parting words, but I’m coming back. So I guess my final thoughts are there’s a lot being talked about right now about soft landing, and if I could, I would stricken said phrase from our parlance, and here’s why. Because ultimately Congress didn’t say, we want you to just touch 2% inflation and full employment, like a touchdown. They said, we want you to produce a sustainable economy with 2% inflation and price stability. Now, we’re not the only game in town for producing this, but I just want to leave you all with this. We’re on the job even if you see 2% inflation. We’re on the job even if you see the labor market settling out. The goal that we have that, the reason I get up every morning and think about how much responsibility we have and how committed we are to it. Is because it’s about a durable expansion.

And with a durable expansion that has low inflation, price stability, and full employment, ultimately, the economy that runs like that sits in the background of people’s minds and in the foreground of people’s minds are building their career, raising their families, contributing to their communities, and that’s an economy that works for all.

Carolyn Holly:

Will you join me in thanking Mary Daly for coming back to Boise, Idaho and sharing with us, and I can think you can tell from this crowd right here, we welcome you anytime.

Mary C. Daly:

I’ll be back. I always love coming to Boise. First place I ever traveled for the District, and I’ll make it the last place I’ve traveled should I move on.

Carolyn Holly:

Our doors are open.

Mary C. Daly:

Okay. Thank you.

Carolyn Holly:

Thank you everybody for coming.

Summary

San Francisco Fed President Mary C. Daly discussed monetary policy, Idaho’s growing economy, and the Fed’s commitment to its dual mandate goals during a moderated conversation with former KTVB anchor Carolyn Holly at Boise State University.

During the in-district visit, President Daly and Abby McLennan, vice president and regional executive of the Salt Lake City branch toured College of Western Idaho and met with students, instructors, and administrators.

Quick Clips

From the Event

Sign up for notifications on Mary C. Daly’s speeches, remarks, and fireside chats.

About the Speaker

Mary C. Daly is President and Chief Executive Officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. In that capacity, she serves the Twelfth Federal Reserve District in setting monetary policy. Prior to that, she was the executive vice president and director of research at the San Francisco Fed, which she joined in 1996. Read Mary C. Daly’s full bio.