Remarks as prepared for delivery.

Introduction

Good morning.

It’s great to be in New York again and to have the opportunity to speak with you about the economy and monetary policy. I very much appreciate the invitation, and I look forward to a lively discussion.

Now, instead of starting with monetary policy, I’m going to begin with a story.

Last week, I was walking in my neighborhood. A young father, with a stroller, a toddler, and a dog called out to me. He had a question. “President Daly, are you declaring victory?”

I immediately said no. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) won’t be satisfied until inflation is at our 2 percent goal.

But as it turns out, that wasn’t what he meant.

What he wanted to know was that we wouldn’t stop there. He wanted low inflation, a healthy labor market, and a durable expansion. He wanted a chance to catch up and then advance. A chance to recoup what high inflation took from him. And an opportunity to build his career, family, and community. An opportunity to be better off.

As a policymaker, that has always been my objective—to deliver the foundations for that type of economy. And with inflation easing and the economy back on a sustainable track, that objective can be our focus.

Today, I will discuss the progress we’ve made in bringing inflation down and the importance of looking beyond a “soft landing.” Aspiring to a durable expansion with sustained price stability.

Before I go on, let me remind you that the views I express are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of anyone else in the Federal Reserve System.

A More Balanced Economy

Let me start with where we are right now. The economy is clearly in a better place. Inflation has fallen substantially, and the labor market has returned to a more sustainable path. And the risks to our goals are now balanced. This is significant improvement from just two years ago.

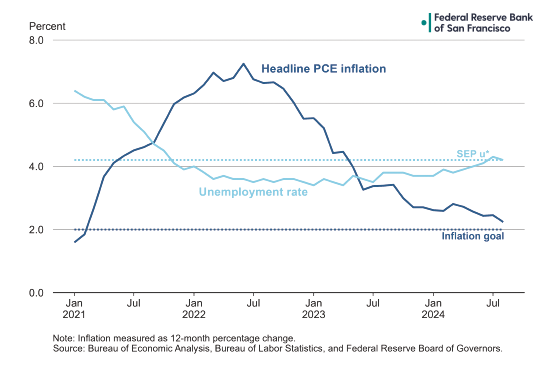

This figure makes the point (Figure 1). Since March of 2022, when the FOMC began raising interest rates, inflation has declined from over 7 percent at its peak to just over 2 percent in the most recent readings. Inflation expectations—what people believe about the future—have come down as well, confirming that households, businesses, and markets see the progress and believe the disinflationary process will continue.1

At the same time, the labor market has cooled. Most labor market indicators are now at or near their pre-pandemic values, and the unemployment rate is hovering around a level judged to be sustainable over the longer run.2 All this means that the labor market has largely normalized and is no longer a major source of inflation pressures.3

Figure 1: Inflation and unemployment since January 2021

Recalibrating Policy

Of course, as conditions improve, policy needs to adjust.

Remember, during the fight to bring inflation down, the FOMC raised rates aggressively and kept monetary policy tight, historically so.4 And then each month that inflation and inflation expectations fell, policy became tighter in real terms.

So, the FOMC needed to recalibrate, and did so at the September meeting. I see this recalibration as “right-sizing,” recognizing the progress we’ve made and loosening the policy reins a bit, but not letting go. Even with this adjustment, policy remains restrictive, exerting additional downward pressure on inflation to ensure it reaches 2 percent.

Making these adjustments to match the economy we have is crucial. It prevents the mistake of over-tightening and ensures we are supporting both of our goals.

Continued progress is not guaranteed. We must stay vigilant and be intentional, continually assessing the economy and balancing both of our mandated objectives: fully delivering on 2 percent inflation while ensuring that the labor market remains in line with full employment.

That is a soft landing.

Beyond A Soft Landing

But as the dad in my neighborhood reminded us, this is only part of what people need. What households, businesses, and communities really want is a durable economy, with sustained growth, a good labor market, and low inflation.

High inflation chipped away at real incomes and purchasing power, intensifying the challenges of overcoming pandemic disruptions.5 Everyone felt it. But the burden fell particularly hard on low- and moderate-income families, who spend a disproportionate share of their resources on shelter, food, and fuel, where price increases have been especially large.6

Businesses have also struggled, especially small- and medium-sized firms that have been saddled with back-to back challenges of pandemic closures, supply bottlenecks, labor shortages, and high inflation.7

A durable and sustained expansion allows both families and businesses to recoup their losses and rebuild incomes and wealth that raise their economic well-being.8

And all of this helps communities, which depend on households and businesses to thrive.

So, is a durable expansion possible?

History says yes.

Again, the data tell the story (Figure 2). Compared to recent history, the current expansion is still relatively young.

Figure 2: Length of expansions

I’ve had the benefit of working at the Federal Reserve during the two longest expansions on record—the 1990s and the pre-pandemic period. During both, remarkable things occurred. Businesses thrived, workers got jobs, and gains in household earnings, income, and wealth were widely shared.9

The expansion just prior to the pandemic was especially impressive: nearly 11 years, 10 years and 8 months to be precise, the longest on record. And I saw firsthand what the data tell us—sustainable growth with low inflation delivers opportunities.10

Robust labor markets brought a broader group of workers into jobs.11 More and more Americans entered or reentered the labor force, wages and incomes rose, and inequality fell.12 Even wealth gains were widely shared, with low net-worth families generally seeing the largest growth in their holdings.13 All of this meant better conditions for households and businesses across the country.

We’ve already seen some of the same patterns play out in our current expansion. Labor force participation for prime-age workers has reached new highs.14 Earnings gaps between high- and low-wage workers have closed somewhat.15 And after rising initially during the pandemic, household income inequality has fallen back down more recently.16

The bottom line: sustained expansion helps all Americans.

The Economy We Deserve

In the coming months and years, there will almost certainly be economic bumps, disturbances, and scares. And the Federal Reserve cannot fully prevent shocks from having an impact. But barring such events, and with the right monetary policy mix, we can help create the conditions for enduring growth.

The most important trait in a central banker is the ability to look ahead. To keep an eye on today and an eye on tomorrow.

The work to achieve a soft landing is not fully done. And we are resolute to finish that job.

But that cannot be all we’re after.

Ultimately, we must strive for a world where people aren’t worried about inflation or the economy. A world where people have time to catch up, and then to get ahead.

That, as I told the young father, is my version of victory. And that’s when I will consider the job truly done.

Footnotes

1. Bundick and Smith (2024). The most recent data also show muted inflation expectations for the near term and longer term; see, for example, the Cleveland Fed’s inflation expectations data page (https://www.clevelandfed.org/indicators-and-data/inflation-expectations).

2. See the FOMC’s September 2024 Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) (Board of Governors 2024). The September unemployment rate of 4.1 percent was a touch below the SEP median estimate of the natural unemployment rate of 4.2 percent.

3. Lansing and Petrosky-Nadeau (2024; update pending for late October). See also Powell (2024).

4. The recent federal funds rate peak maintained from July 2023 through mid-September 2024 was at the highest level in over 20 years, since early 2001.

5. Guerreiro et al. (2024), Stantcheva (2024).

6. Klick and Stockburger (2024).

7. See Chamber of Commerce (2023) and Federal Reserve Banks (2024).

8. Real wages and incomes have been rising, but most households are yet to fully make up the earlier losses. See Guzman and Kollar (2024) and usual weekly earnings from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpswktabs.htm).

9. For the details of the 1990s expansion, see various chapters in Krueger and Solow (2001).

10. See Daly (2020) for details and a broader discussion in the context of long-term inequality trends and the role of the Federal Reserve.

11. Aaronson et al. (2019).

12. Aaronson et al. (2019), Robertson (2019), Guzman and Kollar (2024).

13.Bhutta et al. (2020).

14. Prabhakar and Valletta (2024).

15. Autor, Dube, and McGrew (2023). Updated numbers from the BLS Usual Weekly Earnings series confirm that earnings gaps have generally remained low during the current expansion.

16. Guzman and Kollar (2024).

References

Aaronson, Stephanie, Mary C. Daly, William Wascher, and David W. Wilcox. 2019. “Okun Revisited: Who Benefits Most from a Strong Economy?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, pp. 333-404.

Autor, David, Arindrajit Dube, and Annie McGrew. 2023. “The Unexpected Compression: Competition at Work in the Low Wage Labor Market.” NBER Working Paper 31010, March.

Bhutta, Neil, Jesse Bricker, Andrew C. Chang, Lisa J. Dettling, Sarena Goodman, Joanne W. Hsu, Kevin B. Moore, Sarah Reber, Alice Henriques Volz, and Richard A. Windle. 2020. “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2016 to 2019: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Federal Reserve Bulletin 106(5), September.

Bundick, Brent, and A. Lee Smith. 2024. “Despite High Inflation, Longer-Term Inflation Expectations Remain Well Anchored.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Bulletin (May 31).

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2024. “Summary of Economic Projections.” September 18.

Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America. 2023. “Small Business Index Reaches Post-Pandemic High as Business Owners See Improving Economy.” Report, September 20.

Daly, Mary C. 2020. “Is the Federal Reserve Contributing to Economic inequality?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2020-32 (October 19).

Federal Reserve Banks. 2024. “2024 Report on Employer Firms: Findings from the 2023 Small Business Credit Survey.” Report, March 7.

Guerreiro, Joao, Jonathon Hazell, Chen Lian, and Christina Patterson. 2024. “Why Do Workers Dislike Inflation? Wage Erosion and Conflict Costs.” NBER Working Paper 32956 (revised October 2024).

Guzman, Gloria and Melissa Kollar. 2024. “Income in the United States: 2023.” U.S. Census Bureau Report P60-282, September 10.

Klick, Joshua and Anya Stockburger. 2024. “Examining U.S. Inflation across Households Grouped by Equivalized Income.” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, July.

Krueger, Alan B., and Robert M. Solow, eds. 2001. The Roaring Nineties: Can Full Employment Be Sustained? New York: The Russell Sage Foundation and the Century Foundation Press.

Lansing, Kevin and Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau. 2024. “Staying on Course: Reducing Inflation along a Nonlinear Phillips Curve.” SF Fed Blog, February 21.

Powell, Jerome. 2024. “Review and Outlook.” Speech presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, WY, August 23.

Prabhakar, Deepika Baskar and Robert G. Valletta. 2024. “Why Is Prime-Age Labor Force Participation So High?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-03 (February 5).

Robertson, John. 2019. “Faster Wage Growth for the Lowest-Paid Workers.” FRB Atlanta Macroblog, December 16.

Stantcheva, Stefanie. 2024. “Why Do We Dislike Inflation?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring.