In a study earlier this year (Abdelrahman and Oliveira 2023), we examined household saving patterns since the onset of the pandemic recession. Our study showed that households rapidly accumulated unprecedented levels of excess savings—defined as the difference between actual savings and the pre-recession trend—relative to previous recessions. Our analysis suggested that some $500 billion of the $2.1 trillion in total accumulated excess savings remained in the aggregate economy by March 2023.

Since then, data revisions show noticeable changes in household disposable income and consumption, while new data releases indicate that consumer spending picked up in the second quarter. Our updated estimates suggest that households held less than $190 billion of aggregate excess savings by June. There is considerable uncertainty in the outlook, but we estimate that these excess savings are likely to be depleted during the third quarter of 2023.

Households spent more and saved less

The Bureau of Economic Analysis recently revised its previous estimates to show household disposable income was lower and personal consumption was higher than previously reported for the fourth quarter of 2022 and first quarter of 2023. The combined revisions brought down the Bureau’s measure of aggregate personal savings by more than $50 billion. In addition, second-quarter data indicate that household spending continued to grow at a solid pace.

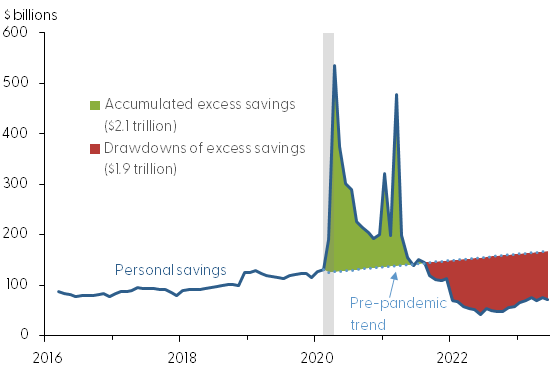

Figure 1 shows that estimates of accumulated excess savings, in nominal terms, totaled around $2.1 trillion by August 2021 when it peaked (green area). Since then, aggregate personal savings have dipped below the pre-pandemic trend, signaling an overall drawdown of pandemic-related excess savings. The drawdown on household savings was initially slow but started to accelerate in 2022 and has remained around $100 billion per month on average.

Figure 1: Aggregate personal savings versus the pre-pandemic trend

Note: Excess savings calculated as the accumulated difference in actual de-annualized personal savings and the trend implied by data for the 48 months leading up to the first month of the 2020 recession as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The red area in Figure 1 shows our updated estimate for cumulative drawdowns, which reached more than $1.9 trillion as of June 2023. This implies that there is less than $190 billion of excess savings remaining in the aggregate economy. Should the recent pace of drawdowns persist—for example, at average rates from the past 3, 6, or 12 months—aggregate excess savings would likely be depleted in the third quarter of 2023.

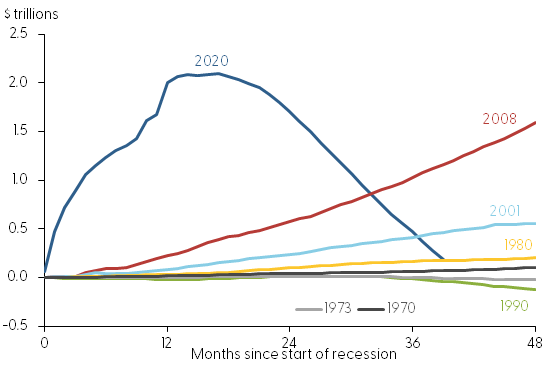

In Figure 2, we update our Economic Letter’s depiction of the monthly progression of excess savings following post-1970 recessions. The rapid accumulation and subsequent drawdown of excess savings following the onset of the pandemic recession contrasts starkly with prior recessions. This contrast holds true when the data are adjusted for inflation, as well as when we define excess savings as a share of trend savings or as a percent change from pre-recession periods.

Figure 2: Aggregate excess savings following onset of recessions

Note: Excess savings calculated as the accumulated difference between actual personal savings and the trend implied by data for the 48 months leading up to the first month of each recession as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. For simplicity, the two recessions in the early 1980s are combined.

Uncertainty and final thoughts

Estimates of aggregate excess savings are filled with uncertainty because they are highly sensitive to the methodology used and the assumptions made about the pre-pandemic trend. For example, recent work by de Soyres, Moore, and Ortiz (2023) uses personal saving rates–rather than levels–to estimate excess savings in the economy. The authors estimate that the stock of excess savings was depleted in the first quarter of 2023.

Others estimate that a much smaller share of excess savings has been spent so far. For example, Briggs and Pierdomenico (2023) estimate that households still hold a considerable amount of excess savings but argue that these holdings will not be a major driver of spending growth going forward primarily because of the front-loaded dynamics of spending responses to changes in income and wealth, among other factors. Additional uncertainty arises when trying to estimate how excess savings are dispersed along the income distribution (see, for example, the discussion in Aladangady et al. 2022.)

Overall, despite differing methodologies and assumptions, the existing body of work on household savings following the pandemic recession firmly points to the rapid accumulation and drawdown of excess savings in the United States. Our estimates suggest that a relatively small amount—around $190 billion—remains in the overall economy, and we expect the aggregate stock of excess savings will likely be depleted during the third quarter of 2023—that is, the current quarter—for which initial data will be released later.

Download data (Excel document, 24 kb)

References

Abdelrahman, Hamza, and Luiz E. Oliveira. 2023. “The Rise and Fall of Pandemic Excess Savings.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2023-11, (May 8).

Aladangady, Aditya, David Cho, Laura Feiveson, and Eugenio Pinto. 2022. “Excess Savings during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, October 21.

Briggs, Joseph, and Giovanni Pierdomenico. 2023. “Excess Savings: Still Large, but Less Important.” Global Economics Analyst, Goldman Sachs, June 30.

de Soyres, Francois, Dylan Moore, and Julio Ortiz. 2023. “Accumulated Savings during the Pandemic: An International Comparison with Historical Perspective.” FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, June 23.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.