A substantial and unexpected rise in women’s labor force participation rates over the past few years has been a key factor spurring rapid labor force growth. In particular, Hispanic women have made a disproportionately large contribution to post-pandemic growth in prime-age women’s participation rates. Analysis shows that this group’s increase was driven by both a rise in labor market participation over the life cycle within generational cohorts and notably higher participation rates among younger generations than older generations’ participation when they were the same age.

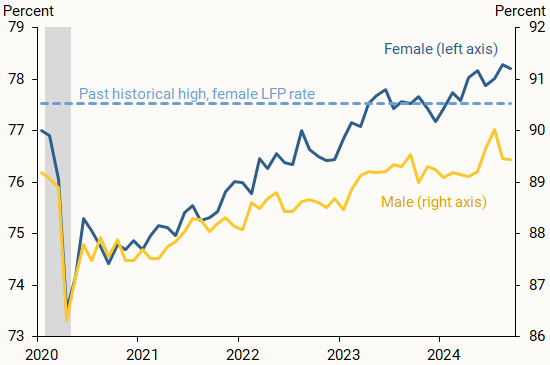

Labor force participation among people in their prime working years, ages 25 to 54, surged following the pandemic to levels not seen in years—in some cases, to record highs. Men’s participation, which had been declining for decades, returned to levels not seen since 2009 (see Prabhakar and Valletta 2024). Meanwhile, in early 2023 women’s participation surpassed its previous peak and has increased further since then. In fact, for nearly a decade, prime-age women have driven the growth in overall prime-age labor force participation.

In this Economic Letter, we investigate which demographic groups are driving this striking increase in prime-age women’s labor force participation during the recent recovery. We find that Hispanic women, particularly those born between 1990 and 1999, are participating in the labor force at notably greater rates than earlier generations. The trend could be explained by the increasing number of Hispanic women earning a college degree. This shift is also reflected in an increasing share of Hispanic women entering higher-paying and less-cyclical industries and occupations such as professional services. The change may reflect a longer-term shift in their labor supply that could persist beyond the current economic expansion.

Labor force participation rates by race and ethnicity

The labor force participation (LFP) rates among people ages 25 to 54 have grown significantly since the pandemic, with women contributing more to the increase than men. Figure 1 shows that, since January 2021, the participation rate for prime-age women has surged 3.5 percentage points, increasing from 74.7% to 78.2%. As of September 2024, that was nearly double the 1.8 percentage point rise among men.

Figure 1

Prime-age labor force participation rates

Note: Dashed blue line indicates the previous historical high for prime-age women’s LFP. Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Examining the data across racial and ethnic groups provides some insights into what is driving the growth in prime-age women’s participation. We use microdata collected under the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey to examine trends in women’s LFP rates for four groups, which we define to be mutually exclusive for our analysis: White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American and Pacific Islander.

Relative to their respective rates in January 2021, Hispanic prime-age women had the largest LFP rate growth, with 6.1 percentage points. Asian American and Pacific Islander women followed with 5.3 percentage points, then Black women with 4 percentage points, and White women with the lowest growth of 2.6 percentage points.

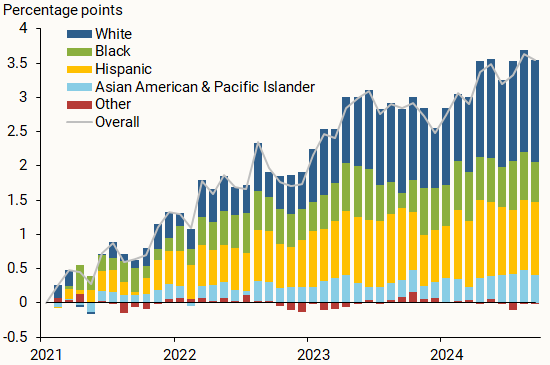

Contributions to labor force growth since 2021

To examine the relative contributions of each racial and ethnic group’s different rates of growth to the overall change in prime-age women’s participation, we account for each group’s share in the population. That is, we calculate these contributions by determining the percentage point difference in LFP rates for each demographic group between January 2021 and each subsequent month and then multiplying that difference by the group’s population share as of that month. The contributions, shown as colored bars in Figure 2, sum approximately to the percentage point increase in the overall LFP rate since January 2021 (solid gray line).

Figure 2

Contributions to women’s LFP growth since January 2021

Note: Colored segments represent the monthly population share-weighted contribution of groups to the change in overall prime-age women’s LFP rate since January 2021. Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and authors’ calculations.

Hispanic women (gold bars) have made a disproportionately large contribution to prime-age women’s LFP rate growth relative to their population share. Specifically, Hispanic women accounted for nearly one-third (1.1 percentage points) of the 3.5 percentage point increase in the overall prime-age women’s LFP rate since 2021 but represent only 17% of the prime-age women population. By contrast, White women contributed about 43% of the increase (dark blue bars), substantially less than their 56% share of the prime-age women population.

Generational differences in labor force participation

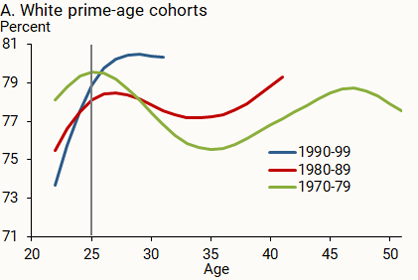

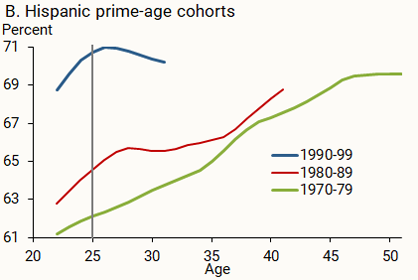

Given that White and Hispanic women have contributed the most to recent labor participation growth among prime-age women, we focus on these groups to look at differences across birth-year cohorts. Figure 3 shows participation rates over time for White and Hispanic women born within three distinct birth-year periods: 1970–79 (green line), 1980–89 (red line), and 1990–99 (blue line). We chose these generational cohorts such that they include all prime-age women as of 2024, with the youngest women in the 1990–99 cohort being age 25 in 2024 and the oldest women in the 1970–79 cohort being age 54 in 2024. We plot participation rates for each cohort starting at age 22 to show early labor market participation decisions.

Figure 3

Labor force participation rates for three cohorts of White women and Hispanic women

Source: Authors’ calculations using Current Population Survey microdata from January 1992 through September 2024. Data are smoothed using a Hodrick-Prescott filter.

Note first that White women (panel A) had higher participation rates across all ages and cohorts than Hispanic women (panel B). The lowest rate for White prime-age women is about 75% for the 1970–79 cohort when they’re in their mid-30s. On the other hand, the highest rate for Hispanic prime-age women is 71% for the 1990–99 group in their late 20s.

Second, the figures show that younger generations have generally been participating in the labor market at higher rates than their predecessors at the same age. This is most apparent for the youngest cohort of Hispanic women. Participation is up nearly 9 percentage points compared with when women in the 1970–79 cohort were in their late 20s and 6 percentage points relative to the 1980–89 cohort. While this pattern also exists among successive cohorts of White women, it is much less pronounced.

Much of the overall growth we observe in Hispanic women’s participation can be attributed to the youngest cohort. Between January 2021 and the second half of 2023, the 1990–99 birth cohort contributed nearly two-thirds (2.9 percentage points) to the 4.6 percentage point increase in Hispanic women’s LFP rate.

The third pattern in the figure is the pronounced increase in the rate of participation for Hispanic women as they move through their prime working years. For example, the 1970–79 cohort’s participation rate rose from 62% at age 25 to nearly 70% in their early 50s (panel B, green line). The LFP rate for women in the 1980–89 cohort rose sharply in their late 30s and early 40s, more quickly than the previous cohort at the same age (panel B, red line). This contrasts with the life-cycle pattern for the same cohorts of White women (panel A); their participation at ages 25 and 50 are about the same, around 78%. That is, the rate of participation for White women dips nearly 4 percentage points in their late 20s to early 30s for the 1970–79 cohort, before recovering in their late 30s and early 40s. This pattern does not appear to occur among cohorts of Hispanic women. The dip among White women could be attributable to temporary exits from the labor force for childcare reasons (Shenhav 2023).

Summing up, the rise in Hispanic prime-age women’s participation appears to be driven by both increased participation in the labor market over the life cycle within cohorts and increased participation across successive cohorts—with the youngest cohort displaying the most substantial increased participation early in their working lives.

What’s behind higher participation among Hispanic women?

While educational attainment has risen across generations for all races and sexes, the generational gains for Hispanic women have been relatively large. The share of Hispanic women with a college degree at age 30 in the 1990-99 cohort is double that of the 1970–79 cohort. The rate of increase was slower across generations of White women with the share holding a college degree at age 30 rising by about one-fourth.

The higher participation rate among our youngest Hispanic women’s age group can be attributed in part to the rise in college education and in part to the increased participation rate among non-college-educated women. Hispanic women’s LFP rate for those who hold a college degree is around 84%, similar to the 87% for White women with a college degree. At the same time, participation for Hispanic women without a college degree is also significantly higher for the 1990–99 cohort compared with older peers at a comparable age: 66% participation at age 25, compared with 60% for both older cohorts when they were that age.

An additional factor—and also a consequence of greater educational attainment—is that younger generations of Hispanic women are entering higher-paying, less cyclically sensitive industries and occupations compared with their older counterparts. In 2000, just 29% of Hispanic women ages 25 to 30 were employed in professional services. By 2024, this number rose to 40%. Simultaneously, personal and retail employment among Hispanic women fell from 30% to 25% across the same years. The occupational composition of employment tells a similar story, showing that Hispanic women in professional and management occupations increased from 21% in 2000 to 36% in 2024. It is worth noting that, while other racial and ethnic groups experienced similar educational and occupational trends during the same time period, the changes are more pronounced among Hispanic women.

Conclusion

The labor force participation rate for prime-age women has been rising, particularly among Hispanic women. Further investigation detailed in this Letter shows that the growth in labor force participation among Hispanic prime-age women comes from increasing participation over the life cycle within generations, along with an increase in participation across generations. The latter is most notable for the generation born between 1990 and 1999 and likely reflects a significant increase in educational attainment. These developments, accompanied by a move toward employment in less cyclical jobs, are likely to reflect a longer-term shift in labor supply that may last well beyond the current economic expansion.

References

Prabhakar, Deepika Baskar, and Robert G. Valletta. 2024. “Why Is Prime-Age Labor Force Participation So High?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-03 (February 5).

Shenhav, Na’ama. 2023. “How Much Do Work Interruptions Reduce Mothers’ Wages?” FRBSF Economic Letter 2023-25 (October 2).

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org