Cash transfers are important fiscal policy tools for both advanced and developing countries. A study of one of the world’s largest cash transfer programs—Brazil’s Bolsa Familia—highlights the potentially large, positive, and persistent effects on the regional economy. Estimates using 2004-2019 data show that Brazilian states receiving 1% of GDP in extra transfers grew at least 2 percentage points faster in the first year. The transfers generate substantial increases in regional formal and informal employment. These effects are larger than those documented in advanced countries like the United States.

More than 130 countries use direct cash payments to boost the economy during downturns, alleviate poverty, provide social insurance, and support other development goals. Around 500 million people worldwide were receiving some type of cash assistance before the COVID-19 pandemic (World Bank 2018), and that number has grown in the years since.

In principle, the effects of cash transfers on regional GDP could be large, small, or negative depending on the mechanisms at play. The effects of cash transfers on local output could be large if the transfer is spent on locally produced goods, and, if businesses are slow to reset their prices or wages, increased demand could result in higher output rather than higher prices. The effects could also be large if the regional economy is in a recession. On the other hand, cash transfers may have zero or negative effects if households save the transfer or spend it on goods produced in other regions. How long countries provide cash transfers also is important because they can have larger effects on spending and labor supply when households perceive them to be long-lasting.

This Economic Letter summarizes our analysis in Mendes et al. (2023) on Bolsa Familia, one of the world’s largest cash transfer programs, which was implemented in Brazil in late 2003. Our study evaluates empirically the program’s impact on state-level GDP as well as on formal and informal employment. Our results suggest that cash transfers may have larger effects on short-run growth in developing economies than were previously reported for advanced economies such as the United States.

Cash transfers in the Bolsa Familia program

Bolsa Familia (BF) is a conditional cash transfer program created in late 2003 to provide a vast expansion of social protection benefits in Brazil. BF is one of the largest social programs in the world, reaching 14 million poor families—about one-fourth of the Brazilian population—costing about 0.5% of the country’s GDP. The program makes direct monthly cash transfer payments to low-income households, conditional on health checkups and children’s school attendance.

The scale, duration, and institutional features of the program make it a useful case to examine the macroeconomic effects of cash transfers in a developing country.

Measuring the impact of cash transfers

We estimate the effects of the BF program on output and employment using variation in transfers across Brazil’s 27 states (including the federal district) over the 2004–2019 period. In general, it is difficult to identify whether a change in cash transfers causes a change in regional economic growth or the causality runs in the opposite direction. For instance, larger transfers can be in response to higher regional economic growth, or procyclical, due to the government having more funds available when the economy is growing. On the other hand, transfers could be countercyclical due to policymakers’ efforts to stimulate a slowing economy or because more people become eligible for assistance from antipoverty programs like BF during recessions.

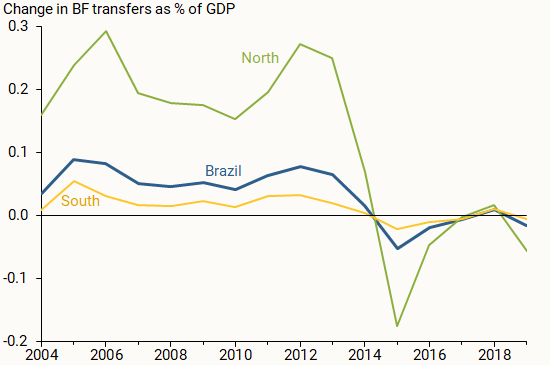

To address this identification problem, we use variation in the sensitivity of each state’s BF transfers to program funding at the national level. Figure 1 shows overall BF transfers in Brazil (blue line), as well as changes as a percent of state GDP in Brazil’s poorer states in the north (green line) and richer states in the south (gold line). The figure illustrates that the poorer northern states tend to be more sensitive to national BF transfer changes than the richer southern states. For example, an increase of national BF transfers of 1% of the national GDP would lead to an increase in BF transfers to the northern states of around 3% of the state GDP. In contrast, the same change in the national BF program would lead to a much smaller increase of BF cash transfers as a share of the state GDP in the richer southern states.

Figure 1

Sensitivity of Brazilian regions to variation in cash transfers

Source: Author’s calculations with data from Brazilian Statistics Bureau (IBGE) and the Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger (MDS).

We use these different regional sensitivities to changes in national BF transfers to identify the causal effects of cash transfers on GDP and employment. Our approach relies on the assumption that national BF transfers do not change in response to economic conditions in particular states.

One advantage of studying fiscal policy at the state level is that we can estimate the effects on both formal and informal employment. Informal employment is common in developing countries: in Brazil, about half of total employment is informal, reaching up to two-thirds in the poorer north and northeast states. However, data on informal employment are generally unavailable at the municipal level in Brazil.

Effects of cash transfers on Brazil’s state economies

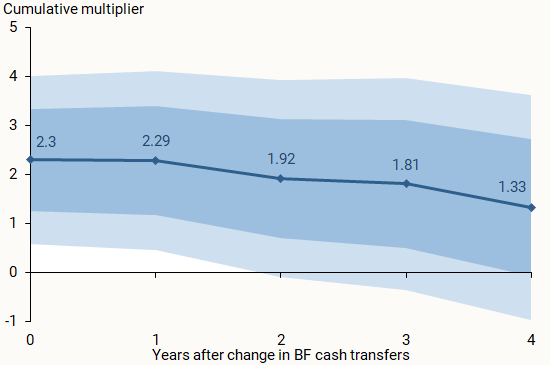

To examine how cash transfers affect state economies in Brazil, we focus on a relative output multiplier. A relative output multiplier measures the changes in relative economic output in a state that receives an extra 1 Brazilian real (1 R$) of transfers than other states receive. As the blue line in Figure 2 shows, we estimate an initial relative output multiplier of 2.3. That is, when a state receives an extra 1 R$ of BF transfers relative to other states, output in that state tends to be 2.3 R$ higher than other states that did not receive the extra transfer.

Figure 2

Cumulative effects of cash transfers on relative GDP

Figure 2 plots standard-error bands around the point estimate, containing the actual value roughly 90% (lighter shading) and 68% (darker shading) of the time if the model is correctly specified. The bands show that our estimates are within 90% statistical certainty in the first year.

We also compute a cumulative relative multiplier, which is the cumulative change in relative inflation-adjusted GDP over a specific period in response to the cumulative increase in relative cash transfers of 1% of inflation-adjusted GDP over the same period. Figure 2 extends the cumulative multiplier out to four years after a change in BF spending and shows that the positive effects persist over this period. In addition, we find that much of the relative output increase comes from the nontradables sector, suggesting that the multiplier is operating by stimulating demand for local goods and services.

Our multiplier estimate for Brazil is fairly large compared with the estimated multipliers of one-third for temporary transfer payments and around 1.5 for permanent Social Security transfers across U.S. states estimated by Pennings (2021). It is also larger than the relative government spending multiplier of 1.5 in the United States, as estimated by Nakamura and Steinsson (2014). Compared with existing evidence in other developing countries, our estimate of above 2 is similar to the multipliers in Egger et al. (2022), who estimate the effects of a large one-time transfer in a randomized control trial across low-income households in Kenyan villages. One potential explanation for such large effects is that low-income people may not work less when they receive cash transfers and might even work more as the transfers make them healthier and reduce financial stress (Banerjee et al. 2024).

In addition, we find that an extra 100,000 R$ in BF transfers to a Brazilian state adds over four more formal sector jobs and also boosts informal employment. Since informal employment is associated with low earnings and sometimes lower hours, we construct an alternate measure of effective total employment called formal-wage equivalent employment that takes into account the lower earnings of the informal workers. We find that a state that receives an extra 100,000 R$ generates about seven formal-equivalent jobs. Although these employment estimates are imprecise, the fact that BF transfers stimulate more formal-equivalent jobs than formal-sector jobs suggests that accounting for informal employment is important when considering the overall macroeconomic effects of the cash transfer program. Finally, our estimates of the job multipliers imply a much smaller cost per job than in the United States, which is to be expected given that the average wage in Brazil is much lower than in the United States.

Conclusion

This Letter summarizes a new analysis of the effects of cash transfers on regional output and employment growth in a developing country using the data from Brazil’s Bolsa Familia program. The macroeconomic focus of the analysis—at the state level with many years of policy changes—allows us to directly estimate GDP multipliers and use data on informal employment in addition to formal employment. The macroeconomic effects of cash transfers appear to work through demand for locally produced goods and services. The estimates for Brazil are also fairly large compared with estimates for the United States.

While fiscal stimulus is not the primary goal of antipoverty cash transfer programs, our results show that an unanticipated positive side effect of these programs is they can stimulate both regional economic growth and employment. This is particularly important because the regions receiving the largest transfers are some of the most disadvantaged, and many governments have historically struggled to develop those regions. Moreover, within the context of our study, concerns about cash transfers reducing economic output in those regions by reducing labor supply appear to be unfounded. However, our results do not necessarily imply that cash transfers are an effective form of stimulus in developing countries at the national level, as this depends on the overall responses of monetary policy, taxation, and other policies, which are beyond the scope of this Letter.

References

Banerjee, Abhijit, Dean Karlan, Hannah Trachtman, and Christopher R. Udry. 2024. “Does Poverty Change Labor Supply? Evidence from Multiple Income Effects and 115,579 Bags.” NBER Working Paper 27314.

Egger, Dennis, Johannes Haushofer, Edward Miguel, Paul Niehaus, and Michael Walker. 2022. “General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers: Experimental Evidence from Kenya.” Econometrica 90(6), pp. 2,603–2,643.

Mendes, Arthur, Wataru Miyamoto, Thuy Lan Nguyen, Steven Pennings, and Leo Feler. 2023. “The Macroeconomic Effects of Cash Transfers: Evidence from Brazil.” FRBSF Working Paper 2024-02.

Nakamura, Emi, and Jon Steinsson. 2014. “Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from U.S. Regions.” American Economic Review 104(3), pp. 753–792.

Pennings, Steven. 2021. “Cross-Region Transfer Multipliers in a Monetary Union: Evidence from Social Security and Stimulus Payments.” American Economic Review 111(5), pp. 1,689–1,719.

World Bank. 2018. The State of Social Safety Nets 2018. World Bank Open Knowledge Repository.

Views are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the World Bank, its executive directors, or the countries they represent.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org